Category: Caselets

Brazilian Business Leaders Push Back on an Illiberal President

Time Period: 2019-2023Location: Brazil, especially Rio de JaneiroMain Actors: Federation of Industries of the State of São Paulo, Instituto Ethos, Sistema BTactics: - Declarations by organizations and institutions - Signed...

Veterans Defend Standing Rock Protesters

Time Period: December 2016Location: United States, North Dakota (Standing Rock Reservation)Main Actors: Veterans, Veterans Stand for Standing RockTactics - Protest - Non-violent occupation - Assemblies of protest The Standing Rock...

Venezuelan Military Officers Refuse Honors from a Dictator

Time Period: June 2000Location: VenezuelaMain Actors: Venezuelan Military OfficersTactics - Selective social boycott Venezuela began a long, sad road towards authoritarianism and economic crisis during Hugo Chávez’s presidency (1999-2013). The...

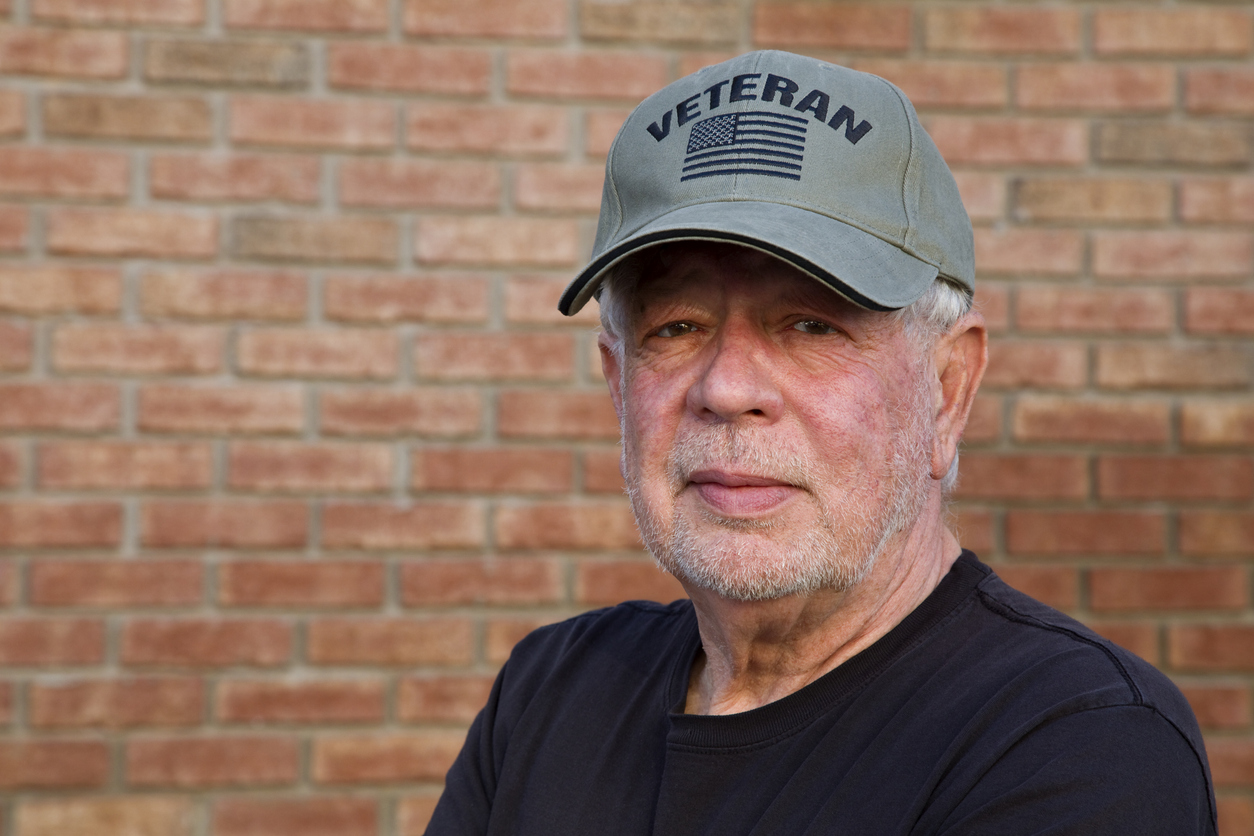

A “Wall of Vets” Protects Free Expression in Portland

Time Period: Summer 2020Location: Portland, Oregon (and then spread across USA)Main Actors: Wall of Vets Facebook GroupTactics - Protective Presence - Nonviolent Interjection Following the police killing of George Floyd...

US Military Leaders Affirm Their Commitment to Democracy

Time Period: January 2021Location: Washington, DCMain Actors: US Joint Chiefs of StaffTactics - Letters of Opposition or Support On January 6th, 2021, the United States faced a direct threat to...

Ukrainian Veterans Save Lives Through Quiet Diplomacy

Time Period: December 2002 - December 2004Location: UkraineMain Actors: General Volodymyr Antonets, veterans & officers in the Ukrainian security forcesTactics - Dialogue/engagement - Fraternization - Withholding or withdrawal of allegiance...

Sikh Langars Feed Protests for Farmers’ Rights

Time Period: November 2020 - December 2021Location: Delhi, IndiaMain Actors: Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee & other Sikh organizationsTactics - Protest camps, nonviolent occupation - Declarations by organizations and institutions...

Hungarian Evangelicals Resist Democratic Backsliding

Time Period: 2010-2019Location: Budapest, HungaryMain Actors: Hungarian Evangelical Fellowship (HEF), Pastor Gábor Iványi.Tactics - Declarations by organizations and institutions - Selective social boycott - Protective presence - Signed public statements...

Polish Bishops Refuse to Support Authoritarianism

Time Period: 2016-2023Location: Poland, especially WarsawMain Actors: Polish Episcopal ConferenceTactics - Declarations by organizations and institutions - Public speeches - Boycotts of social affairs Poland became less free and democratic...

Activating Faith: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference Fights for Freedom

Time Period: Civil Rights Era, 1955-1970sLocation: United StatesMain Actors: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); affiliate churches; Civil Rights organizersTactics - Protest–teach-ins to educate and encourage participation - Mass action–sharing...