By Mónica Roa, Puentes

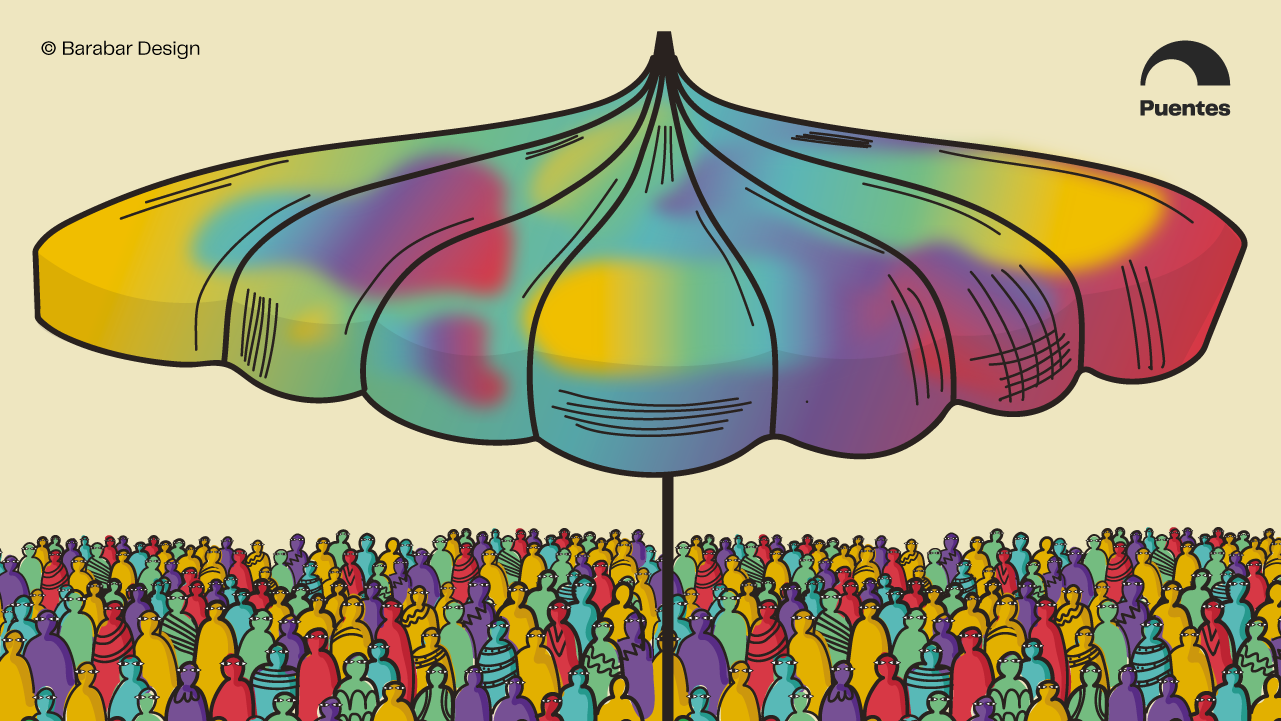

In a world where public spaces for social interaction are vanishing and digital platforms promote isolation through hyper-personalized consumption of entertainment and services, at Puentes, we propose interconnection as a narrative antidote to authoritarianism. In my previous blog, I argued that the narrative of extreme individualism erodes community bonds, fuels excessive competition, and sows fear of others—paving the way for the concentration of power and the sacrifice of rights and freedoms. In contrast, narratives of interconnection weaken fear-based narratives by showing us that we have more in common than what divides us—and that we cannot survive without the web of relationships that sustains us. By strengthening our awareness of interdependence, these narratives can counter authoritarianism, foster solidarity, and build communities capable of imagining a shared future.

But for this narrative to have a real impact, telling stories about the world we want is not enough—we must embody interconnection in how we see ourselves and organize. Narrative work isn’t just about crafting stories to make sense of reality; it’s also about shaping the lived experiences and the sense of possibility we collectively nurture. This challenges us to move from theory to practice, weaving expansive connections across movements, geographies, knowledge systems, and new audiences to build a “larger us” capable of driving change.

If we want interconnection to be a transformational force against authoritarianism, we must expand the boundaries of our identity beyond organizational logos, single-issue campaigns, and geographical silos that have long structured our social change efforts. Interconnection and the creation of a “larger us” are two sides of the same coin: interconnection provides the narrative framework (everything is linked), while a “larger us” gives us the organizing strategy (how we act on that truth). Together, they challenge the foundations of authoritarianism by showing that wellbeing is achieved not through isolation, but through integration—not through fear, but through collaboration. Those of us committed to democracy, human rights, and social, racial, gender, and climate justice must embrace this story of interconnection and reject the false divisions between people and planet, between neighbors and strangers, and between communities deemed worthy and unworthy of protection.

In this blog, I will explore how to move beyond the logic of “us-versus-them” toward a “larger us”—building and amplifying narratives of interconnection that strengthen our ties and expand our capacity for collective action.

1. Us vs. Them: Beware of the Trap!

Authoritarian narratives thrive by dividing society into warring factions. In 1933, as Germany’s economy collapsed, Adolf Hitler rose to power by blaming Jews and communists for the country’s crisis. In 2025, the playbook hasn’t changed much. From Donald Trump’s manufactured panic over a supposed migrant invasion, to Viktor Orbán’s crusade against so-called gender ideology, to the criminalization of poor youth during the war on drugs in Latin America, authoritarian actors of all stripes use the same tried-and-true tactic: divide society into a virtuous “us” and a blameworthy “them.” It’s the narrative of fear deployed as a strategy for power, where the scapegoats may change, but the mechanics remain the same—manufacture enemies to tighten control.

They know exactly what they are doing. By framing society as a battlefield between good and evil, authoritarians tap into the most primal parts of our brains. As linguist and cognitive scientist George Lakoff explains, fear activates the amygdala, our brain’s survival center, shutting down critical thinking and making us more susceptible to sectarianism. Once trapped in this survival logic, we become more willing to give up our freedoms in exchange for empty promises of security.

It becomes a vicious cycle: the more fear we feel, the more we depend on those who stoke it. History has shown this repeatedly—manufactured panic justifies mass surveillance, censorship, repression, and the concentration of power in the hands of those who claim to protect us. What’s most dangerous about this strategy isn’t just the erosion of democracy—it’s how it strips us of our shared humanity by convincing us that “the other” is a threat, rather than part of “us.”

This narrative works because it simplifies chaos, reducing complex issues like inequality or climate change to an easy-to-digest story: “They” are the problem. That “they” could be anyone—immigrants, Black people, trans people, Muslims, journalists, Jews, the so-called gay lobby, climate radicals, elitist progressives, woke culture, or even, as caricatured during recent U.S. elections, women with cats and no children. Worse still, it distracts from authoritarian power grabs by criminalizing dissent. Just look at Orbán’s portrayal of LGBTQ+ communities as corrupting children. At the same time, it erodes solidarity, breeding distrust and divisions—even within social movements—preventing the formation of strategic alliances. Instead of uniting to confront the true sources of oppression—concentrated power, structural inequality, and the unsustainability of predatory capitalism—we get stuck in endless purity tests and infighting, ceding power to those who fear our unity most.

Even more troubling, this logic is a trap even for those committed to inclusion. It doesn’t matter who draws the line between a virtuous “us” and a wicked “them”—the outcome is the same. Every time we use this narrative, we activate fear, deepen sectarianism, and fall back into an individualistic mindset that weakens collective action. In other words, saying “we” are the good ones and “they” are the bad ones ultimately serves them—even if we are right. As long as we play that game, the beneficiaries of polarization stay in power because their strategy doesn’t rely on which side wins, only that society remains divided.

And here’s the paradox: even pointing out this dynamic risks reinforcing it. Every time we frame those who sow fear as a distinct “them,” we inadvertently reproduce the same logic we’re trying to dismantle. So how do we name what we are up against without reinforcing the game that sustains it?

A counter-narrative with real transformative power is that of a “larger us.” This vision pulls us out of the survival logic and activates our higher brain functions—empathy, critical thinking, and the capacity to solve problems together.

It means recognizing the humanity and concerns of those who think differently, rather than dismissing or demonizing them. When we label people as ignorant or reduce their entire identity to one harmful behavior (“you are sexist” instead of “that behavior is sexist”), we deny them their full humanity—and their capacity to grow and change. This logic not only fuels polarization, but it also feeds the division that authoritarians exploit to consolidate power.

This isn’t about avoiding critique — it’s about changing the game. Calling out injustice will always be part of our path, but it can no longer be the destination. Changing the game means inviting people on a collective journey where the goal isn’t to defeat “the other,” but to build a shared future rooted in dignity, interconnectedness, and the common good. It’s a journey where we make space for experimentation, allow ourselves to be surprised by unexpected alliances, and take joy in discovering new ways of doing, imagining, and inspiring.

Last year, during a gathering of feminist leaders from around the world, an African colleague shared the deep pain she feels facing the situation in Uganda. She said she wanted those in power to fear us again. The facilitator picked up on her comment and asked, “So what should we do to make them fear us again?”

Some of us — mostly coming from the narrative space — felt uneasy with framing our purpose through fear. Another colleague, who is a Black, queer, African woman, reminded us that fear has been a constant companion in her struggle, and that ignoring it would be naïve. Our discomfort wasn’t about pretending that fear would suddenly vanish from political life; it was about resisting the temptation to make it the guiding framework of our work.

Our purpose is to inspire people — despite their fears — to use their individual and collective power to build the world we know is possible and desirable. It does little good if authoritarians fear us, but it doesn’t translate into dignity, wellbeing, and coexistence for our communities.

2. The Virtuous Circle of a “Larger Us”

Interconnection and building a “larger us” are inseparable. Interconnection is the narrative framework: a principle revealing how all life, social systems, and natural phenomena are intertwined in a web of shared causes and consequences. This isn’t abstract. Growing inequality, climate breakdown, and the lack of aspiration among younger generations are all symptoms of the same truth—no suffering, nor its solution, exists in isolation. When we narrate the world through this lens of interconnection, we dismantle myths of individual or national self-sufficiency and reveal that wellbeing isn’t a scarce resource to hoard—it’s a balance we cultivate together.

The second side, building a “larger us,” is the action framework. It calls us to expand the boundaries of identity, circles of care, and limits of solidarity to reflect that interconnection. The challenge for those of us doing narrative work—which, in truth, is all of us—is to commit to a practice that creates a virtuous cycle, where narrative inspires action, and action redefines what is possible.

Stories don’t just reflect reality—they help shape it. In a world marked by isolation and polarization, where differences often seem like insurmountable barriers, we must remember the power of storytelling to challenge prejudice and help us see ourselves in one another. By amplifying the voices of those who have been pushed to the margins, by showing the humanity of people who think differently from us, by creating stories that make our interconnections visible, we can cultivate a moral imagination that spans time and space—and transform how we perceive one another, from threats into fellow human beings.

One of the most powerful aspects of storytelling is its ability to generate empathy. When we engage with a story, we don’t just follow its events—we emotionally experience what its characters go through. This happens thanks to mirror neurons, which activate both when we perform an action and when we see someone else perform it. In other words, when we see or imagine someone else experiencing an emotion, our brain simulates it, helping us feel what they feel.

This is why we cry during a sad movie, cheer for a character’s victory, or flinch at their pain. Our brains don’t fully distinguish between our own experiences and those of others; when we enter a story, we partially live what the characters live. This is key to empathy, as it helps us connect with people whose realities may seem far from our own.

Research shows that when a story moves us, our brain releases oxytocin — the hormone linked to trust and social bonding — which deepens our sense of connection to the characters. Neuroscience also suggests that the more familiar we become with certain stories and characters, the stronger our neural and emotional connections grow with the communities they represent. In other words, when we make a habit of engaging with inclusive storytelling, we don’t just shift people’s thinking temporarily — we can actually transform perceptions and attitudes over the long term.

Stories act as powerful neurocultural tools. They don’t just trigger our mirror neurons — making us feel another person’s joy or pain as if it were our own — they also shape how we see ourselves and define who belongs in our circle of care. When we tell stories that weave together seemingly distant experiences — whether across geography, like the fight for marriage equality in Spain, Colombia, or Thailand, or across time, like women’s struggles for education, voting rights, or reproductive justice over the past three centuries — we reveal a common thread of needs, aspirations, and vulnerabilities. These narratives don’t just stimulate empathy at a biological level; they also cognitively rewire the boundaries of identity itself, helping us see that what unites us runs deeper than the differences that might otherwise divide us. In recognizing ourselves in others — even when their lives look different from ours — the “I” becomes intertwined with the “we,” creating a sense of belonging rooted not in exclusion but in shared humanity.

At its core, this narrative work is a political act of meaning-making. The boundaries of identity are not natural — they’ve been constructed throughout history by stories that determine who gets to be seen as fully human and who is cast as “other.” Expanding those boundaries by telling stories that highlight what we have in common helps dismantle the narratives that fracture humanity into antagonistic groups. Telling stories from the perspective of a “larger we” is more than just envisioning the world we want to build — one where social, racial, climate, and gender justice are all part of the same project — it’s also a strategy to activate empathy in the brain. The more we do it, the more we enable people to internalize this way of seeing the world, expanding the limits of their empathy and their sense of responsibility. We can picture this process like the ripple effect of a stone falling into water: as it hits the surface, it creates waves that spread outward, extending the reach of its initial impact. It’s a true win-win — a virtuous cycle of solidarity and transformation that only works if we manage to flood the public conversation with these kinds of stories. That is how we will reach the scale needed to challenge and ultimately break the grip of what is perceived as “common sense,” the version of reality long imposed by hegemonic narratives.

In the second part of this article, we’ll share our reflections on how to weave expansive connections across movements, territories, knowledge systems, and new audiences to build this “larger we” — one that inspires collective action. We’ll also share some of the ways we at Puentes are already putting this into practice. Stay tuned!

Originally posted on LinkedIn where it is available in Spanish and Portuguese.