Tag: Civil Resistance

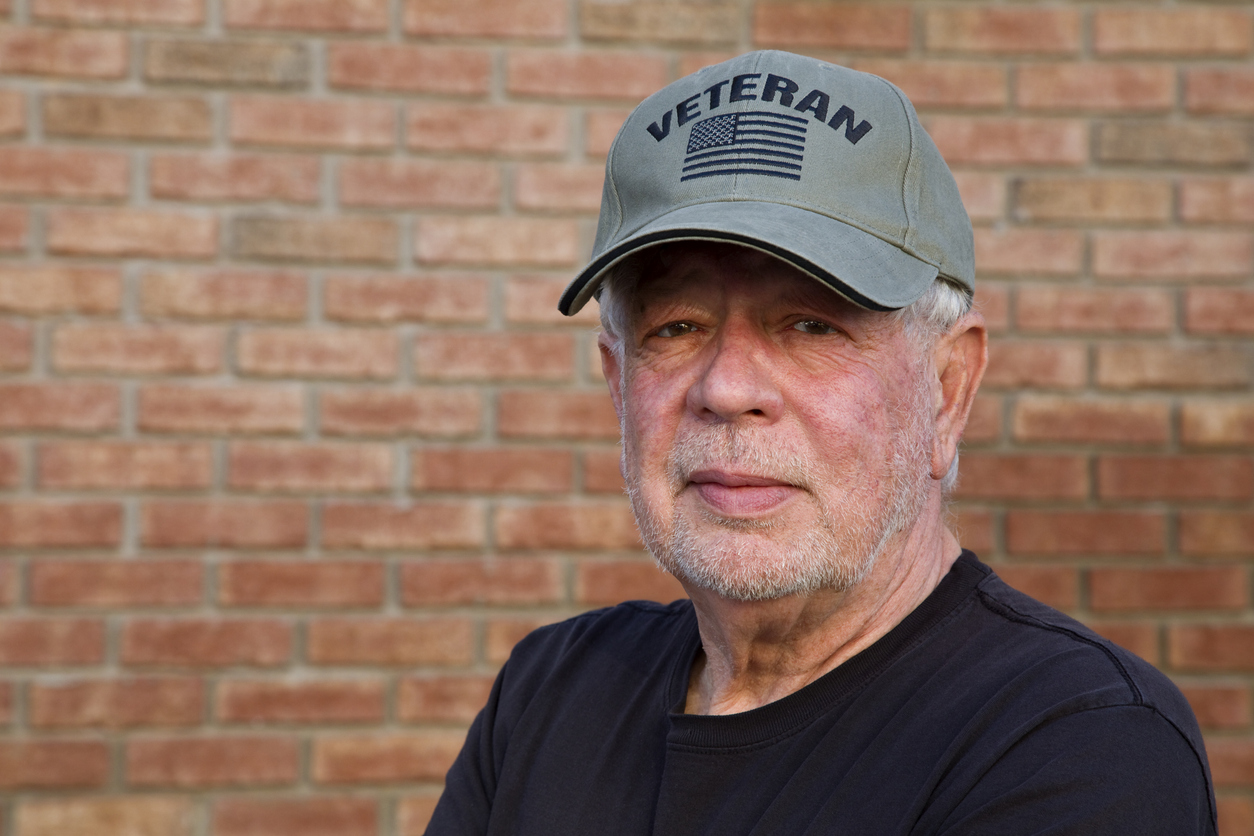

A “Wall of Vets” Protects Free Expression in Portland

Time Period: Summer 2020Location: Portland, Oregon (and then spread across USA)Main Actors: Wall of Vets Facebook GroupTactics - Protective Presence - Nonviolent Interjection Following the police killing of George Floyd...

Hungarian Evangelicals Resist Democratic Backsliding

Time Period: 2010-2019Location: Budapest, HungaryMain Actors: Hungarian Evangelical Fellowship (HEF), Pastor Gábor Iványi.Tactics - Declarations by organizations and institutions - Selective social boycott - Protective presence - Signed public statements...

Polish Bishops Refuse to Support Authoritarianism

Time Period: 2016-2023Location: Poland, especially WarsawMain Actors: Polish Episcopal ConferenceTactics - Declarations by organizations and institutions - Public speeches - Boycotts of social affairs Poland became less free and democratic...

Activating Faith: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference Fights for Freedom

Time Period: Civil Rights Era, 1955-1970sLocation: United StatesMain Actors: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); affiliate churches; Civil Rights organizersTactics - Protest–teach-ins to educate and encourage participation - Mass action–sharing...

Going Pro (Bono): Lawyers Provide Support Against the Muslim Ban

Time Period: 2017-2018Location: United StatesMain Actors: Immigration & constitutional law attorneys; civil rights activists; members of state and national government; business & labor leadersTactics - Civic Engagement - Media Outreach...

“Ask your Doctor if Voting is Right for You!” American Doctors Speak Out on Voting

Time Period: PresentLocation: United StatesMain Actors: The American Medical Association (AMA)Tactics - Declarations by Organizations and Institutions In its June 2022 annual meeting, the American Medical Association (AMA) identified voting...

Lawyers in Pakistan March Against a Military Dictator

Time Period: 2007-09Location: PakistanMain Actors: National Action Committee of Lawyers, Pakistan Bar Association, Supreme Court Bar Association of Pakistan, Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) party, Ifitkhar Muhammad ChaudhryTactics - Assemblies of...

Polish Judges Resist Attacks on the Rule of Law

Time Period: 2016-2021Location: Poland, especially Warsaw; Brussels, BelgiumMain Actors: Polish Judges Association Iustitia, Association of Judges Themis, Wolne Sądy lawyers group, Polish Constitutional Tribunal, Polish Supreme CourtTactics - Civil disobedience...

Labor Unions Join the Fight for Civil Rights

Time Period: Civil Rights Era, 1955-1970sLocation: United StatesMain Actors: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); Labor unionsTactics - Mass action - Boycotts - Protests/Marches - Protective Presence/Witnessing Following the success...

Unions Light the Candle of Democracy in South Korea

Time Period: 2016-2017Location: South Korea, especially SeoulMain Actors: Korean Federation of Trade Unions (KCTU), People’s Action for the Immediate Resignation of President ParkTactics - Vigils - General Strikes In the...