Tag: Protest

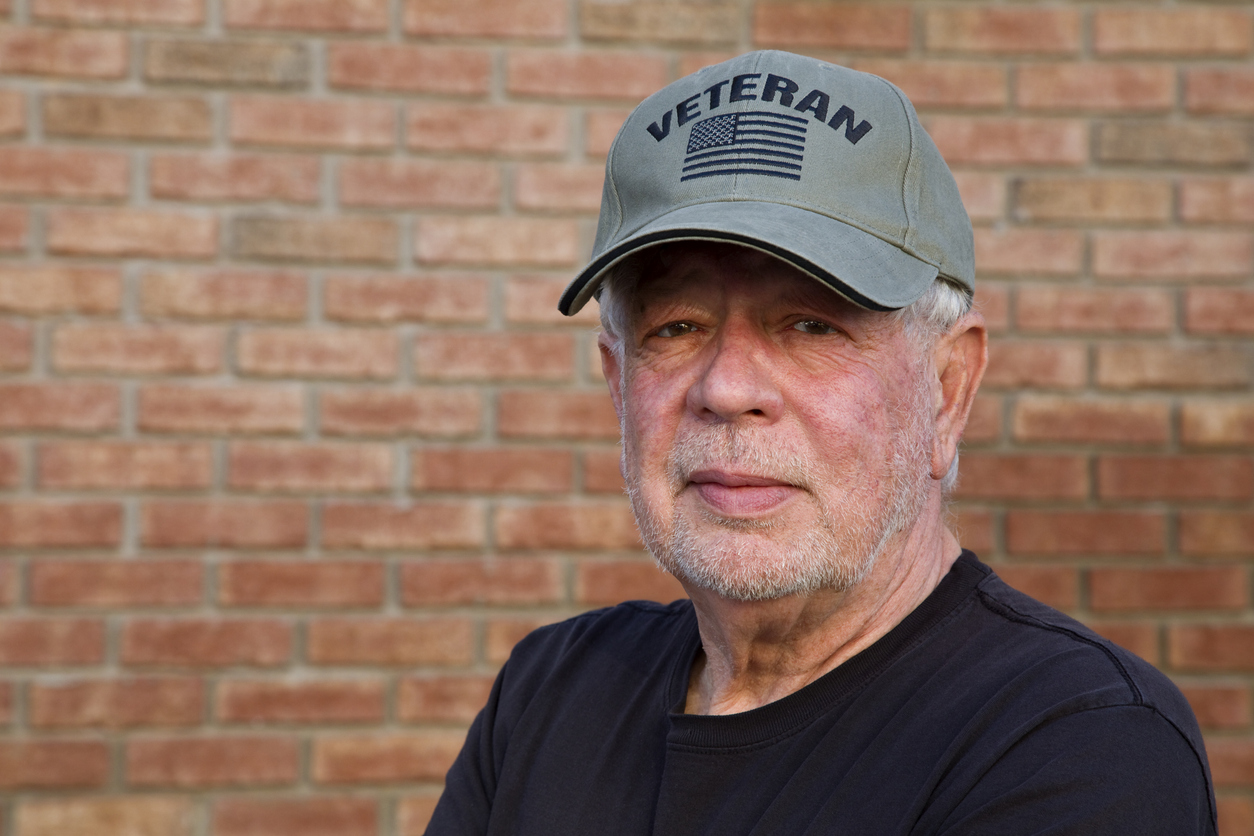

Veterans Defend Standing Rock Protesters

Time Period: December 2016Location: United States, North Dakota (Standing Rock Reservation)Main Actors: Veterans, Veterans Stand for Standing RockTactics - Protest - Non-violent occupation - Assemblies of protest The Standing Rock...

A “Wall of Vets” Protects Free Expression in Portland

Time Period: Summer 2020Location: Portland, Oregon (and then spread across USA)Main Actors: Wall of Vets Facebook GroupTactics - Protective Presence - Nonviolent Interjection Following the police killing of George Floyd...

Sikh Langars Feed Protests for Farmers’ Rights

Time Period: November 2020 - December 2021Location: Delhi, IndiaMain Actors: Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee & other Sikh organizationsTactics - Protest camps, nonviolent occupation - Declarations by organizations and institutions...

Hungarian Evangelicals Resist Democratic Backsliding

Time Period: 2010-2019Location: Budapest, HungaryMain Actors: Hungarian Evangelical Fellowship (HEF), Pastor Gábor Iványi.Tactics - Declarations by organizations and institutions - Selective social boycott - Protective presence - Signed public statements...

Activating Faith: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference Fights for Freedom

Time Period: Civil Rights Era, 1955-1970sLocation: United StatesMain Actors: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); affiliate churches; Civil Rights organizersTactics - Protest–teach-ins to educate and encourage participation - Mass action–sharing...

“Ask your Doctor if Voting is Right for You!” American Doctors Speak Out on Voting

Time Period: PresentLocation: United StatesMain Actors: The American Medical Association (AMA)Tactics - Declarations by Organizations and Institutions In its June 2022 annual meeting, the American Medical Association (AMA) identified voting...

Brazilian Doctors Strike for Healthcare Reform and Democracy

Time Period: 1977-1981Location: BrazilMain Actors: Brazilian Doctor’s UnionTactics - Professional Strike - Slowdown Strike - Marches - Establishing new social patterns In 1964, a military coup overthrew Brazil’s democratically elected...

Lawyers in Pakistan March Against a Military Dictator

Time Period: 2007-09Location: PakistanMain Actors: National Action Committee of Lawyers, Pakistan Bar Association, Supreme Court Bar Association of Pakistan, Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) party, Ifitkhar Muhammad ChaudhryTactics - Assemblies of...

Labor Unions Join the Fight for Civil Rights

Time Period: Civil Rights Era, 1955-1970sLocation: United StatesMain Actors: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); Labor unionsTactics - Mass action - Boycotts - Protests/Marches - Protective Presence/Witnessing Following the success...

Indian Farmers’ Unions Block Roads to Bolster Democracy

Time Period: June 2020 - December 2021Location: India (Punjab & Delhi)Main Actors: Farm Unions, organized under the Samyukta Kisan Morcha (“United Farmers’ Front”)Tactics - Protest camps, nonviolent occupation, sit-ins -...