Tag: Security Sector

The Egyptian Military Defects During the Arab Spring

Time Period: 2011Location: EgyptMain Actors: The Egyptian MilitaryTactics - Withholding or withdrawal of allegiance - Mutinies by government personnel - Protective Presence Between 1981-2011 Egypt was under the authoritarian rule...

The Chilean Security Sector Defects from the Pinochet Dictatorship

Time Period: 1988Location: ChileMain Actors: Fernando Matthei (Air Force General), Rodolfo Stange (General Director of the Police), José Merino (Navy Admiral)Tactics - Withholding or withdrawal of allegiance - Mutinies by...

Philippines Armed Forces Resist a Dictatorship

Time Period: 1982-1986Location: The PhilippinesMain Actors: Armed Forces of the Philippines, Reform of the Armed Forces Movement (RAM), Fidel Ramos, Juan Ponce EnrileTactics - Selective refusal of assistance by government...

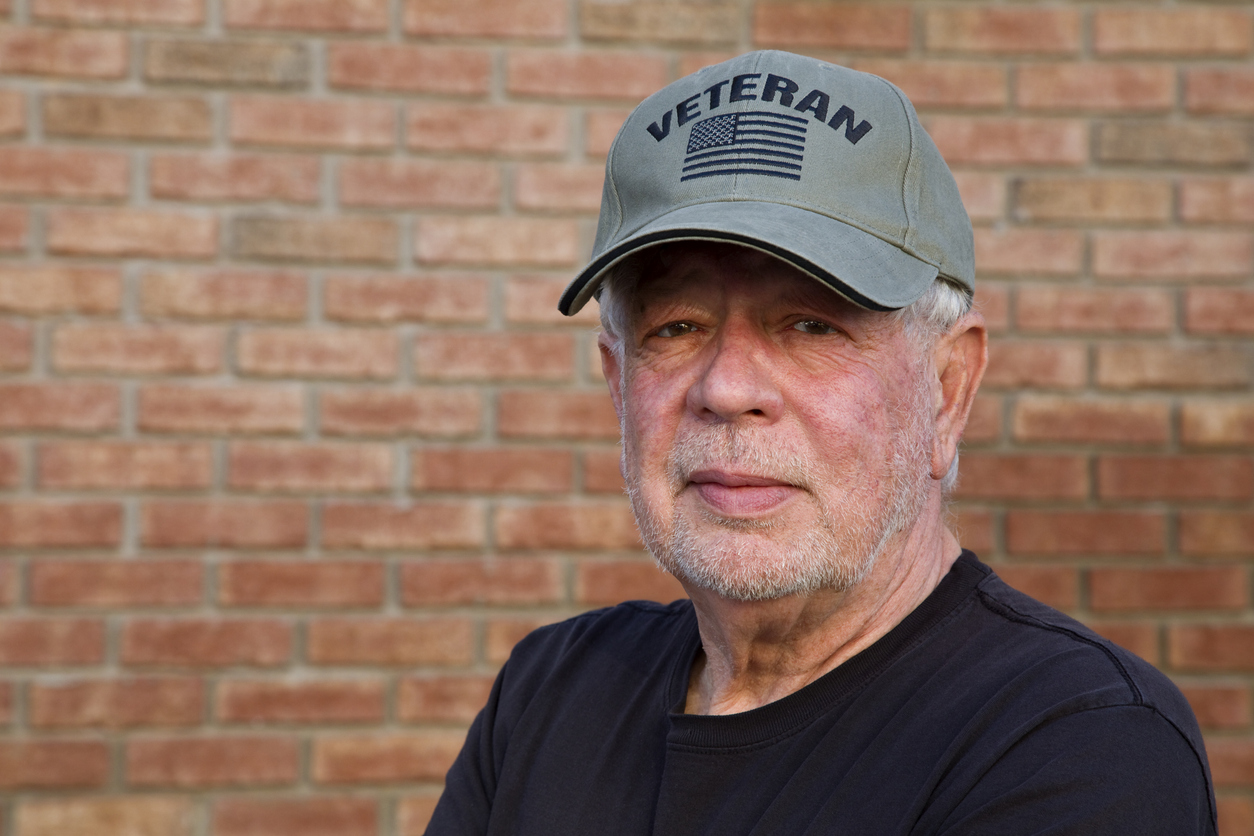

Veterans Defend Standing Rock Protesters

Time Period: December 2016Location: United States, North Dakota (Standing Rock Reservation)Main Actors: Veterans, Veterans Stand for Standing RockTactics - Protest - Non-violent occupation - Assemblies of protest The Standing Rock...

Venezuelan Military Officers Refuse Honors from a Dictator

Time Period: June 2000Location: VenezuelaMain Actors: Venezuelan Military OfficersTactics - Selective social boycott Venezuela began a long, sad road towards authoritarianism and economic crisis during Hugo Chávez’s presidency (1999-2013). The...

A “Wall of Vets” Protects Free Expression in Portland

Time Period: Summer 2020Location: Portland, Oregon (and then spread across USA)Main Actors: Wall of Vets Facebook GroupTactics - Protective Presence - Nonviolent Interjection Following the police killing of George Floyd...

US Military Leaders Affirm Their Commitment to Democracy

Time Period: January 2021Location: Washington, DCMain Actors: US Joint Chiefs of StaffTactics - Letters of Opposition or Support On January 6th, 2021, the United States faced a direct threat to...

Ukrainian Veterans Save Lives Through Quiet Diplomacy

Time Period: December 2002 - December 2004Location: UkraineMain Actors: General Volodymyr Antonets, veterans & officers in the Ukrainian security forcesTactics - Dialogue/engagement - Fraternization - Withholding or withdrawal of allegiance...

THE PILLARS PROJECT: Veterans and Military Families

*By former Director of Applied Research Jonathan Pinckney. Why should veterans and military families care about authoritarianism? American democracy is in a moment of crisis. Long-standing authoritarian trends and practices...

Violence and the Backfire Effect

*This article was written by former Director of Applied Research Jonathan Pinckney. Any movement that seeks to stand up against powerful opposition and advocate on important political issues must be...