Tag: Activism

Inspirational Examples of Principled Collective Action and Loving Defiance

Across the country, groups are using creative forms of collective action and nonviolent defiance to challenge abuses of power and attacks on fundamental freedoms. Key pillars, including faith organizations, unions,...

Buddhist Monks Defect from Myanmar’s Military Dictatorship

Time Period: 2007Location: MyanmarMain Actors: Buddhist monks, All Burma Monks Alliance (ABMA)Tactics - Withholding or withdrawal of allegiance - Slogans, caricatures, and symbols - Assemblies of protest or support -...

Defending Democracy with Humor and Dilemma Actions Tactics

Successful broad-based, pro-democracy fronts often rely on a range of tactics and strategies to engage more people in their cause. One particularly powerful approach is the use of dilemma actions,...

Tunisian Unions Support the Arab Spring

Time Period: 2010-2015Location: TunisiaMain Actors: Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT)Tactics - General strikes - Protective Presence - Assemblies of protest or support Between 1987-2011, Tunisia was an autocracy ruled by...

Teachers in Hungary Oppose Democratic Backsliding

Time Period: 202-2024Location: Budapest, HungaryMain Actors: Tanítanék NGO, Hungarian teachers, students, and parentsTactics - Assemblies of protest or support - Human chains - Destruction of Government Documents Hungarian democracy has...

The Quakers Advance Democracy in the US Civil Rights Movement

Time Period: 1956-1968Location: Montgomery & Birmingham, AL; Prince Edward County, VA; Washington, DC; Cape May, NJ; New Delhi, IndiaMain Actors: American Friends Service Committee, Bayard Rustin.Tactics - Publishing Dissenting Literature...

Brazilian Business Leaders Push Back on an Illiberal President

Time Period: 2019-2023Location: Brazil, especially Rio de JaneiroMain Actors: Federation of Industries of the State of São Paulo, Instituto Ethos, Sistema BTactics: - Declarations by organizations and institutions - Signed...

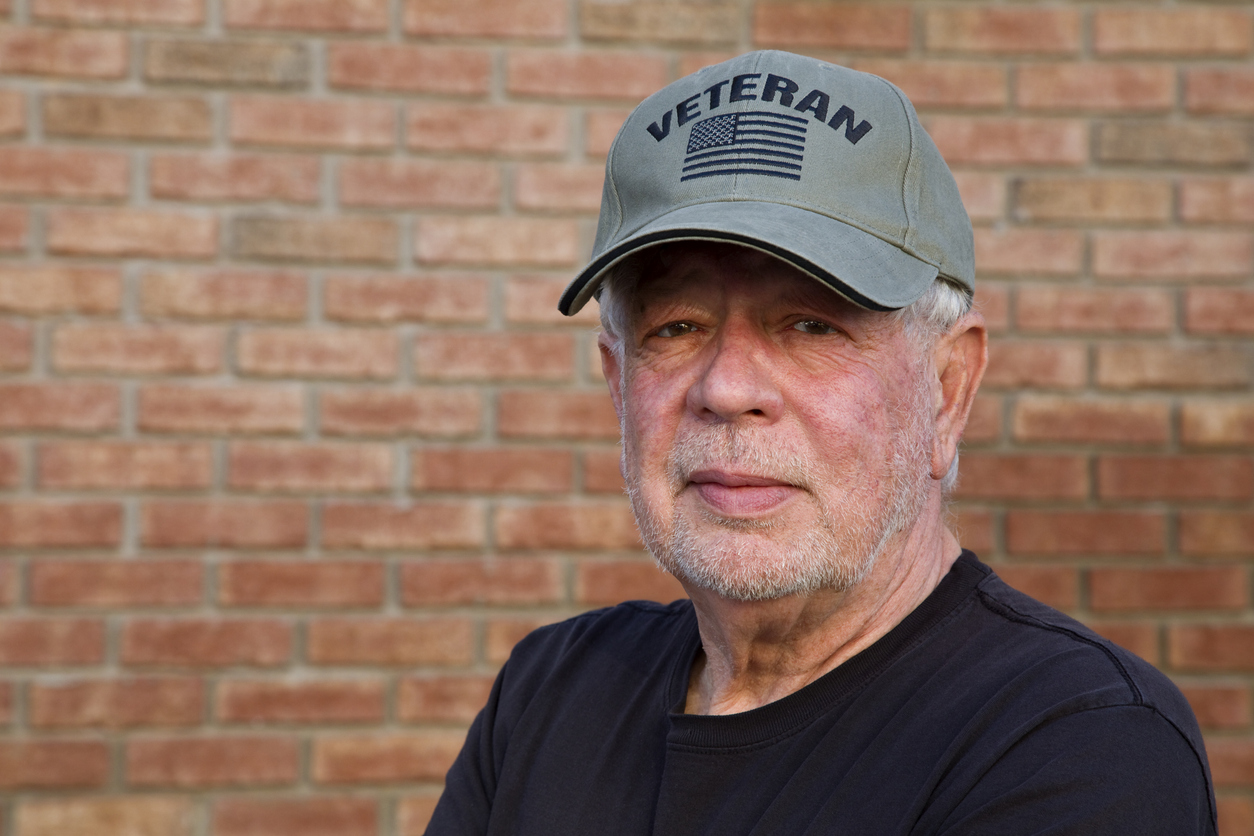

A “Wall of Vets” Protects Free Expression in Portland

Time Period: Summer 2020Location: Portland, Oregon (and then spread across USA)Main Actors: Wall of Vets Facebook GroupTactics - Protective Presence - Nonviolent Interjection Following the police killing of George Floyd...

Activating Faith: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference Fights for Freedom

Time Period: Civil Rights Era, 1955-1970sLocation: United StatesMain Actors: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); affiliate churches; Civil Rights organizersTactics - Protest–teach-ins to educate and encourage participation - Mass action–sharing...

Faith and the Authoritarian Playbook

*This article was written by Chief Organizer Maria J. Stephan and was first published on Sojourners, you can access the full article without a paywall here. How Christians can defend and nurture democracy...