Tag: Nonviolent Intervention

Nonviolence in Action: Why Civil Resistance Works and the Role of Religion

Horizons Chief Organizer, Maria J. Stephan delivered this keynote address at the American Academy of Religion Annual Conference on November 24, 2024. Special thanks to Jin Y. Park, Professor and...

Philippines Armed Forces Resist a Dictatorship

Time Period: 1982-1986Location: The PhilippinesMain Actors: Armed Forces of the Philippines, Reform of the Armed Forces Movement (RAM), Fidel Ramos, Juan Ponce EnrileTactics - Selective refusal of assistance by government...

Teachers in Hungary Oppose Democratic Backsliding

Time Period: 202-2024Location: Budapest, HungaryMain Actors: Tanítanék NGO, Hungarian teachers, students, and parentsTactics - Assemblies of protest or support - Human chains - Destruction of Government Documents Hungarian democracy has...

The Quakers Advance Democracy in the US Civil Rights Movement

Time Period: 1956-1968Location: Montgomery & Birmingham, AL; Prince Edward County, VA; Washington, DC; Cape May, NJ; New Delhi, IndiaMain Actors: American Friends Service Committee, Bayard Rustin.Tactics - Publishing Dissenting Literature...

Brazilian Business Leaders Push Back on an Illiberal President

Time Period: 2019-2023Location: Brazil, especially Rio de JaneiroMain Actors: Federation of Industries of the State of São Paulo, Instituto Ethos, Sistema BTactics: - Declarations by organizations and institutions - Signed...

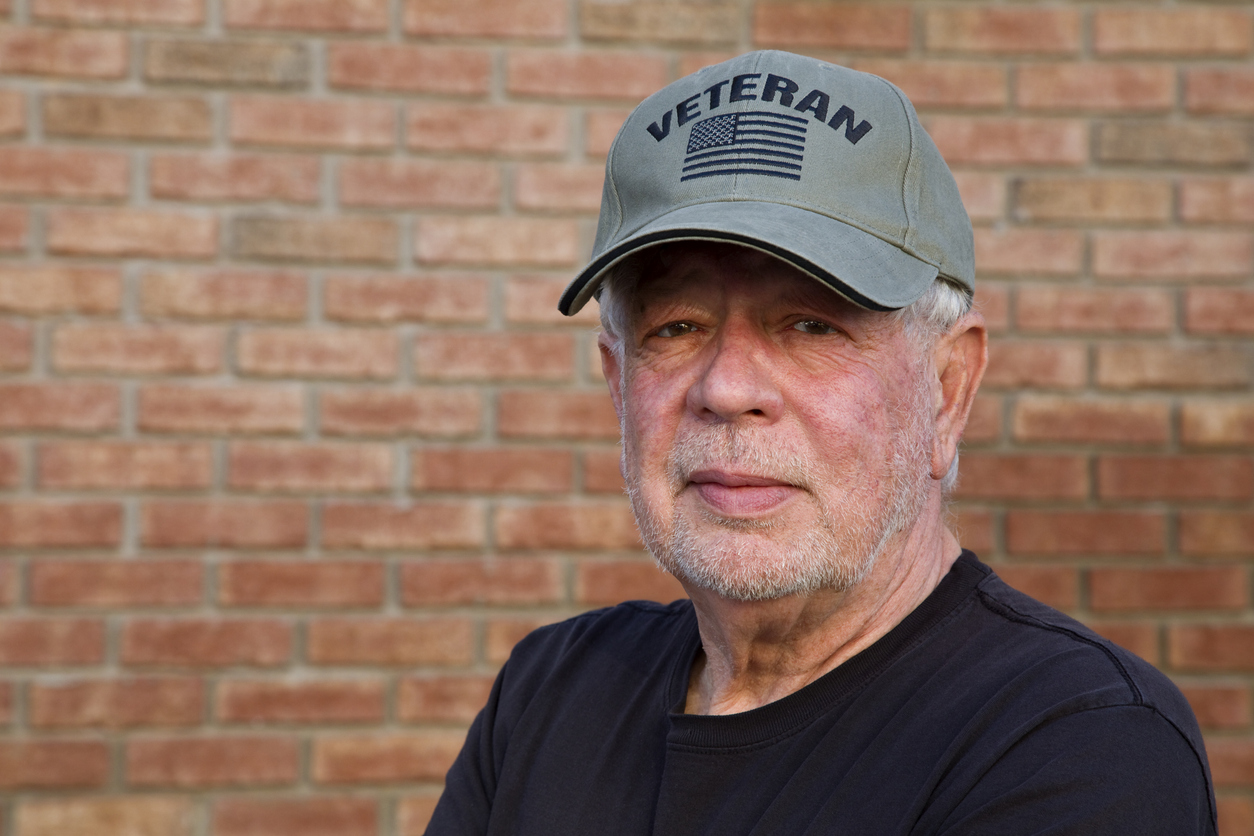

A “Wall of Vets” Protects Free Expression in Portland

Time Period: Summer 2020Location: Portland, Oregon (and then spread across USA)Main Actors: Wall of Vets Facebook GroupTactics - Protective Presence - Nonviolent Interjection Following the police killing of George Floyd...

Sikh Langars Feed Protests for Farmers’ Rights

Time Period: November 2020 - December 2021Location: Delhi, IndiaMain Actors: Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee & other Sikh organizationsTactics - Protest camps, nonviolent occupation - Declarations by organizations and institutions...

Activating Faith: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference Fights for Freedom

Time Period: Civil Rights Era, 1955-1970sLocation: United StatesMain Actors: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); affiliate churches; Civil Rights organizersTactics - Protest–teach-ins to educate and encourage participation - Mass action–sharing...

Southern Baptist Leaders Condemn the January 6th Insurrection

Time Period: 2020-presentLocation: United StatesMain Actors: The Southern Baptist Convention; Russell MooreTactics - Personal Statements - Blogging or Online Article Writing - Newspapers and Journals The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC)...

Lawyers in Pakistan March Against a Military Dictator

Time Period: 2007-09Location: PakistanMain Actors: National Action Committee of Lawyers, Pakistan Bar Association, Supreme Court Bar Association of Pakistan, Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) party, Ifitkhar Muhammad ChaudhryTactics - Assemblies of...