Tag: International

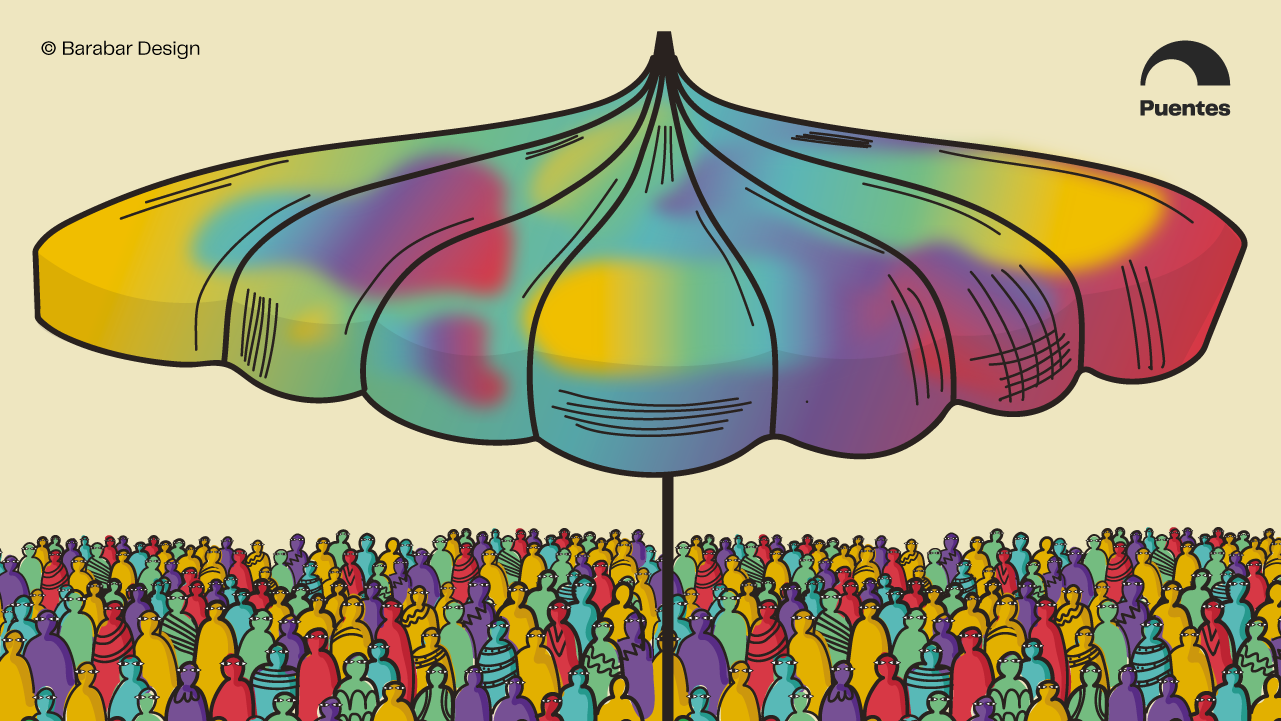

From Interconnection to a “Larger Us”: Expanding Circles of Identity, Care, and Solidarity (Part I )

By Mónica Roa, Puentes In a world where public spaces for social interaction are vanishing and digital platforms promote isolation through hyper-personalized consumption of entertainment and services, at Puentes, we...

Fascism and Isolation vs. Democracy and Interconnection: The Narrative Antidote to Authoritarianism

By Mónica Roa, PuentesOne way to understand our time is as a battleground of intense narrative disputes. On one side, the climate emergency, the impact of artificial intelligence on employment,...

Argentine Catholic Clergy Oppose Javier Milei

Time Period: 2023-presentLocation: ArgentinaMain Actors: Catholic clergy, especially Curas Por la Opción Por Los Pobres (Priests for the Option for the Poor)Tactics - Letters of opposition or support - Prayer...

Buddhist Monks Defect from Myanmar’s Military Dictatorship

Time Period: 2007Location: MyanmarMain Actors: Buddhist monks, All Burma Monks Alliance (ABMA)Tactics - Withholding or withdrawal of allegiance - Slogans, caricatures, and symbols - Assemblies of protest or support -...

The Egyptian Military Defects During the Arab Spring

Time Period: 2011Location: EgyptMain Actors: The Egyptian MilitaryTactics - Withholding or withdrawal of allegiance - Mutinies by government personnel - Protective Presence Between 1981-2011 Egypt was under the authoritarian rule...

The Chilean Security Sector Defects from the Pinochet Dictatorship

Time Period: 1988Location: ChileMain Actors: Fernando Matthei (Air Force General), Rodolfo Stange (General Director of the Police), José Merino (Navy Admiral)Tactics - Withholding or withdrawal of allegiance - Mutinies by...

Resilience and Post-election Management

In the aftermath of elections, whether they bring victory, disappointment, or controversy, movements promoting democracy and human rights often face critical challenges in sustaining momentum and navigating political realities. This...

Lessons from Around the World: Engaging ‘Pillars of Support’ to Uphold and Expand Democracy

*This article was written by Chief Organizer Maria J. Stephan and was first published on Just Security. Efforts in the United States to build a broad, cross-partisan, and cross-ideological pro-democratic front...

Brazilian Religious Leaders and Democratic Backsliding

Time Period: 2019-2023Location: Brazil, especially Rio de JaneiroMain Actors: Brazilian Catholic Church, Brazilian Evangelical pastors (e.g., Henrique Vieira) and civil society groups (e.g., Novas)Tactics: - Declarations by organizations and institutions...

Philippines Armed Forces Resist a Dictatorship

Time Period: 1982-1986Location: The PhilippinesMain Actors: Armed Forces of the Philippines, Reform of the Armed Forces Movement (RAM), Fidel Ramos, Juan Ponce EnrileTactics - Selective refusal of assistance by government...