Tag: Authoritarianism

THE VISTA: April 2022

WHAT WE’RE READING, WATCHING, AND LISTENING TO AT HORIZONS

In April, we joined many friends and colleagues in mourning the sudden loss of Peter Ackerman, a visionary and treasured leader in the field of civil resistance. One concrete way to honor Peter’s memory is to read and help spread his most recent publication the Checklist To End Tyranny, an important resource for anyone who cares about organizing to expand freedom over oppression. Mixed in with this sense of loss is also the great joy we experienced this month, as the Horizons team convened our first in-person gathering of an amazing group of women network leaders. During this time, we shared deeply our individual practices of “sensemaking,” a topic near and dear to us as one of our three lines of work at Horizons. You can read more about these practices in our most recent blog. We are also excited to welcome a new teammate, Nilanka Seneviratne, who joined us April 1 as Director of Operations and Systems!

Horizons continues to curate resources each month that bring together different ideas and perspectives linking issues of democracy, peacebuilding, and social justice. We hope you enjoy the many thought-provoking materials in this month’s VISTA:

READING

Dissent and Dialogue: The Role of Mediation in Nonviolent Uprisings

By Isak Svensson and Daan van de Rizen, U.S. Institute of Peace

While both mediation and nonviolent resistance have been the subject of significant scholarly work, the connection of the two fields has received less attention. Using newly collected data on nonviolent uprisings over several years in Africa, this report explores four distinct challenges: how to determine when the situation is ripe for resolution, how to identify valid spokespersons when movements consist of diverse coalitions, how to identify well-positioned insider mediators, and how to avoid the risk of mediation leading to pacification without transformative social change.

Red/Blue Workshops Try to Bridge The Political Divide. Do They Really Work?

John Burnett, NPR

Using an example of a Braver Angels dialogue in La Grange Texas, this article explores the work of bridgebuilders in the US including some limitations and criticisms of these approaches.

The Racial Politics of Solidarity With Ukraine,

Kitana Ananda, Nonprofit Quarterly

This article delves into the nuances of the racialized response to the war in Ukraine both within the United States and abroad, highlighting existing tensions and different perspectives about the need for an anti-war movement to be aligned with racial justice.

How Companies Can Address Their Historical Transgressions

Sarah Federman, Harvard Business Review

Some multigenerational companies or their predecessors have committed acts in the past that would be anathema today—they invested in or owned slaves, for example, or they were complicit in crimes against humanity. How should today’s executives respond to such historical transgressions? Drawing on her recent book about the effort by the French National Railways to make amends for its role in the Holocaust, the author argues that rather than become defensive, executives should accept that appropriately responding to crimes in the past is their fiduciary and moral duty. They can begin by commissioning independent historians, publicly apologizing in a meaningful manner, and offering compensation on the advice of victims’-rights groups. The alternative is often expensive lawsuits and bruising negotiations with victims or their descendants.

How to Avoid (Unintentional) Online Racism and Shut Down Overt Racism When You See It

Mark Holden, Website Planet

Special thanks to Ritta Blens for sharing this piece for us and our readers! While lengthy, this great article provides a comprehensive breakdown of how racism is showing up online in the US and abroad, as well as statistics for how Americans and others are choosing to respond. The article ends with some helpful recommendations for how organizations, journalists, and individuals can avoid unintentionally racist language, as well as address racism when you see it in your online communities.

WATCHING

A Community-Led Approach to Revitalizing American Democracy

The Horizons Project

During the 2022 National Week of Conversation, The Horizons Project, Beyond Conflict, and Urban Rural Action led a conversation on how communities can lead the way to revitalizing democracy in the US and beyond. You can check out the first part of the event in the link above.

America Needs To Admit How Racist It is

The Problem with Jon Stewart (Video) Podcast

This is a heart-felt discussion on race relations with Bryan Stevenson, civil rights lawyer and founder of Equal Justice Initiative about how racism has poisoned America from the very start. The interview also offers ideas on how the country can reckon with our past and repair the damage it continues to do.

The Neutrality Trap: Disrupting and Connecting for Social Change

Great Reads Book Club (Video) Podcast by Mediate.com

Bernie Mayer and Jacqueline Font-Guzman discuss their wonderful new book, with important reflections from the perspective of conflict resolution professionals about how the social issues that face us today need conflict, engagement, and disruption. Avoiding conflict would be a mistake for us to make progress as a country.

Frontiers of Democratic Reform

The American Academy of Political and Social Science, Democracy in the Balance Series

This recording is the third in a series of discussions on democratic vulnerability and resilience in the United States. The final webinar focused on the practical steps that can be taken to guard against democratic backsliding in the United States and how to bolster the integrity of our democratic institutions. Panelists included Judd Choate (Colorado Division of Elections), Lee Drutman (New America), Hahrie Han (Johns Hopkins University), and Larry Jacobs (University of Minnesota). You can download all the journal articles that served as a basis for this series here.

LISTENING

Podcast: The Whole Person Revolution

David French is a columnist for the Atlantic and the author of Divided We Fall, and Jonathan Rauch is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute and the author of The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth. In this podcast they discuss why the current culture wars have been intensifying and potential ways forward.

Podcast: On Being

Ai-jen Poo and Tarana Burke join each other in conversation for this episode in a series from On Being on the future of hope. They discuss their beautiful friendship that has powered and sustained them as they are leading defining movements of this generation. It’s an intimate conversation rooted in trust and care, and an invitation to all of us to imagine and build a more graceful way to remake the world.

Deva Woodly on Reckoning: Black Lives Matter and The Democratic Necessity of Social Movements

Podcast: Conversations in Atlantic Theory

Deva Woodly from the New School for Social Research has published widely on democratic theory and practice, focusing on the function of public meaning formation and its effect on self and collective understanding of the polity. This podcast explores the role of social movements in democratic life and how we come to produce knowledge from those public conversations.

How Many Americans Actually Support Political Violence?

Podcast: People Who Read People

A talk with political scientist Thomas Zeitzoff, discussing survey results that seem to show an increase in Americans willingness to think political violence is justified, and how that relates to our fears about future violent conflicts and “civil war scenarios” in the United States. The podcast also covers the psychology of polarization, the Ukraine-Russia conflict, and the effects of social media on society in general.

INTERESTING TWEETS

A twitter thread breaking down the recent Jon Haidt article in the Atlantic, Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid.

Check out this overview of new research from Ike Silver and Alex Shaw published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology on how the common tactics people use to avoid taking a stand on hot-button issues can backfire, and the costs of moral neutrality.

Luke Craven reflects on the need for “values alignment” for effective coalition-building versus creating the conditions for “values pluralism.”

Using the Climate Crisis as an example, Prof. Katherine Hayhoe highlights the limitations of fear-based messaging, emphasizing the need to not only describe the problems we are facing as a society, but to also offer actions people can take and hope that change is possible.

An interesting discussion on the implication for journalists and media outlets on the ways their reporting is skewed by the highly polarized, politically informed populace versus most Americans who are not politically engaged and tuning out.

Gabriel Rosenberg is an Associate Professor of Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at Duke University and describes why the new label of “groomer” being thrown at political adversaries is so dangerous.

AND NOW FOR SOMETHING COMPLETELY DIFFERENT

With all the heaviness of the world we want to leave you with something a little different. Music is such a powerful force, it has the power to inspire, celebrate, and even galvanize action. This section won’t always be a song but hopefully it’ll strike a chord with you as you go about your day.

Since Mother’s Day is quickly approaching, we wanted to include a musical tribute to all the mothers out there. And someone who’s music inspired has several of us over the years is Brandi Carlile. Her album By the Way, I Forgive You remains in heavy rotation. So, we present for your enjoyment, The Mother.

Sensemaking

One of the three lines of work of The Horizons Project is “sensemaking.” As organizers and coalition-builders who believe in the power of emergent strategy, the practice of sensemaking is something that we are continually reflecting upon: What is sensemaking? What is its purpose? How do we do it better? How can it drive our adaptation? How can we share what we’re learning and doing with diverse communities?

So, what exactly is “sensemaking” and why is it important to organizers? First and foremost, we acknowledge that we are operating in a world filled with volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (VUCA). Even if we weren’t such a small team, we could never hope to fully wrap our minds (and arms) around this VUCA world. If our goal at The Horizons Project is to provide value and help connect actors within the social change and belonging ecosystem, we must find ways to constantly scan and interpret what’s going on within the system to then strategize, act and adjust as needed. Sensemaking is one of those practices. While there are many methodologies and definitions of sensemaking, we are drawn to the approach of Brenda Dervin that is based on asking good questions to fill in gaps in understanding, to connect with others to jointly reflect on our context and then take action.

For example, when we launched Horizons full time in January, we had no idea that a war in Ukraine would pull us so strongly back into discussions of nonviolent resistance on the international stage; that the stark battle between autocracy and democracy there, and evidence of worsening democratic decline globally would offer an opportunity to reframe the threat to democracy in the US; or, that there would be new-found resonance for concepts of peacebuilding as graphic scenes of war are on display daily. How does what is happening in Ukraine affect Horizons’ work of bridging democracy, peacebuilding and social justice in the US? How does the world’s reaction to Ukraine highlight existing inequities within the system, especially with the racialized dynamics experienced within the outpouring of solidarity? How do we make sense of this huge turn of events, both as individuals, as a team and as a broader community of colleagues, and where we go from here?

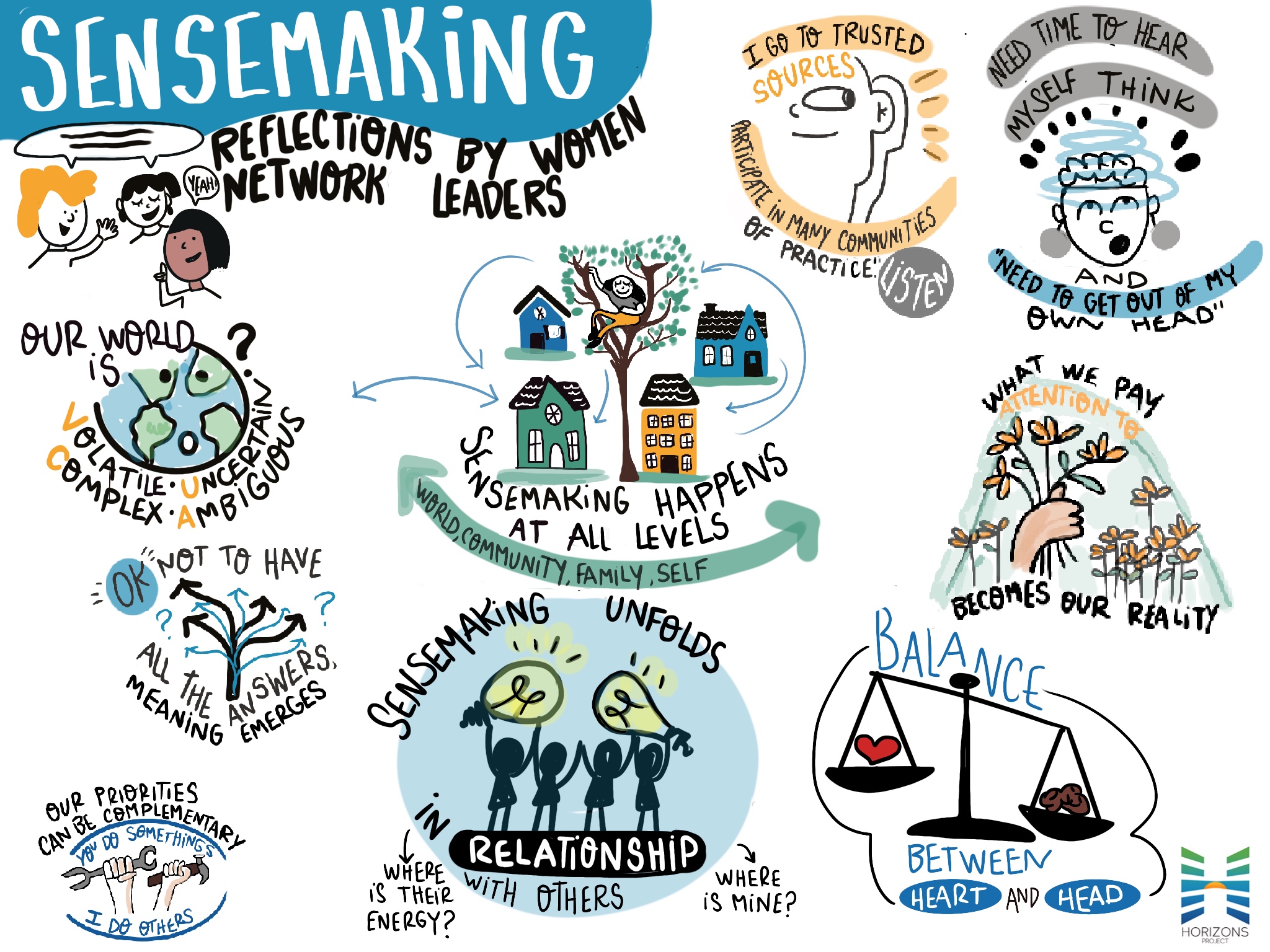

There is no one way to conduct sensemaking. In fact, this word means many things to different practitioners. So, at a recent gathering we asked a group of trusted women in positions of network-wide leadership, to share with us how they think about sensemaking, and what it looks like in practice for them. In a series of short, personal testimonials, Horizons captured these insights in our very first podcast series that we are excited to share.

Several themes emerged from those conversations that we find inspiring, and indicative of the ways women show up as leaders, naturally holding nuance and seemingly contradictory practices that can all be equally true:

Sensemaking is a balance between heart and head. There are many ways of knowing. Placing too much emphasis on analytical skills and tools, and over-intellectualizing how we discern what’s happening around us can be a barrier to also sensing with our emotional intelligence. How do we feel about what’s happing in the world, and how are others’ feeling? Sensemaking involves empathy, and yet radical empathy can also lead to overwhelm and paralysis. Staying within our analytical selves is often a way of protecting our hearts and can help stem the anxiety that comes from uncertainty and volatility. Finding that balance isn’t always easy, but some useful tools are with the arts or through physical activity, finding creative ways to connect to our bodies that can spur new insights.

Sensemaking is not the same as aligning. When working within complex ecosystems with diverse networks and coalitions, we are not always called to make sense in order to identify points of alignment. Having different theories of change is healthy and needed. Naming all of our distinct definitions of the problem and then allowing for a diversity of approaches to unfold is an important network leadership practice. Sensemaking in coalitions does not always have to lead to collective action, but we can uncover shared values when we listen deeply.

I am a person who believes in living as one would want to see a life lived.

Sensemaking takes place externally and internally at all levels. We all go to trusted sources to help make sense of what’s happening around us. Participating in a wide array of communities of practice is useful. We read, we listen, we share. Sometimes we have time to go deep into topics, and other times we are broadly scanning and skimming many sources. But we also need quiet time to hear our own voices through all the noise to take time to process and make sense at the level of our individual selves. This helps us stay coherent with our values and lets our lives represent the world we want to help create.

…the sun blazes

for everyone just

so joyfully

as it rises

under the lashes

of my own eyes,

and I thought

I am so many!

Sensemaking involves awareness of energy flow: It’s okay to feel the discomfort of uncertainty. And yet, we pay careful attention to what gives us energy on a personal level. We are also continually observing what others are doing that seems to be garnering their energy and inspiring others. If we believe that what we focus on eventually becomes our reality, we need to be careful about doom-scrolling or focusing too much on the negative. Broadly, engaging in sensemaking doesn’t mean that we must feel responsible for doing everything and solving every problem ourselves. Elevating the priorities and perspectives of others is a way of supporting collective sensemaking.

Sensemaking is a commitment to being in relationship with others. The human dynamic of building connection is an important practice to create the conditions for effective sensemaking. Playful spaces that allow for us to laugh and let loose – to be embodied human beings as our full selves, this helps to later know who to go to for information and to navigate challenges together. We might think we always have to be “productive”—that we should come together to do mapping of our system, should be identifying intersections for partnership, should be sharing our workplans and formal analysis. But sometimes sensemaking looks like a dance party or just having a meal together. Prioritizing relationships and fun is integral to the work.

Sensemaking includes observing patterns of power and privilege: Being an “outsider” or coming from different cultural, racial or economic backgrounds can help shed light on power dynamics that otherwise might not be seen. Sensemaking by cultivating spaces for individual storytelling, raising the voices of those perspectives not always heard and stitching together many stories to understand common and divergent narrative streams helps to observe those patterns and realign our collective action.

Sensemaking requires authenticity and grace. If we are making sense of “what to do” without a complete picture or levels of certainty (either as individuals or in coalitions), then we will often make mistakes. Giving each other grace to navigate these challenging moments is key: we must allow for incomplete conversations and yet still act; we may choose one imperfect theory to test out and see what happens; we often must agree to disagree and realize that there is not one perfect path that we should all be working on together. Sensemaking in community is also an act of “having each other’s backs” and assuming the best intentions of others doing their best to make sense in their own way. This works best when we act with authenticity, which naturally shines through.

Here are some additional resources on sensemaking to check out:

Horizons Presents (Our podcast, Season One focuses on sensemaking)

Facilitating Sensemaking in Uncertain Times

Thirteen Dilemmas and Paradoxes in Complexity

Energy System Science for Network Weavers

Get a quick glimpse of The Horizons Projects’ conversations on sensemaking in this graphic illustration from artist Adriana Fainstein! You can find more of Adriana’s work here.

THE VISTA: March 2022

WHAT WE’RE READING, WATCHING & LISTENING TO AT HORIZONS

In March, as the war in Ukraine took up so much of our news feeds, we have been inspired by the renewed attention to the need for a global democracy movement and the recognition of our interconnection in a shared fight against authoritarianism. The Horizons team remains committed to elevating the many voices of different disciplines and different perspectives who are committed to finding a way forward together towards a pluralistic, inclusive democracy in the United States and around the world. We have so much to learn from each other. So, in the words of the late and great Secretary Madeleine Albright, “let us buckle our boots, grab a cane if we need one, and march.”

Here are some of the recommendations the Horizons team is inspired to share for this month’s VISTA:

READING

Where Does American Democracy Go From Here?, New York Times Magazine

If we are going to come together to form a larger movement to work for democracy in the United States, we first need to find a common of understanding of the problems we are facing. In this article, six experts across the ideological spectrum discuss how worried we should be out democracy’s future in the US.

How to Resist Manipulation by Embracing All Your Identities: Learning to celebrate complex identities in ourselves and others could help make the world a better place, Greater Good Science Center

“We all contain multiple identities, with those identities vying for primacy in our heads…there is quite a bit of evidence that the world would be a better, more peaceful place if we could hold space for different identities in ourselves and in other people. How can we do that, while resisting efforts to elevate one over all the others in situations of conflict? This article provides some research-based tips.”

Civic Virus: Why Polarization is a Misdiagnosis, The Harwood Institute

Interesting take on the polarization debate. This report posits that Americans don’t really feel polarized or antagonistic toward one another. Rather, that we feel isolated and disoriented, like we are “trapped in a house of mirrors with no way out; in the grips of a perilous fight or flight response.” The authors offer recommendations for “a society that is breaking apart, to give people safe passage to hope” with concrete steps to help us move forward.

Transformative Organizing, Martha Mackenzie, Executive Director of the Civic Power Fund

Coinciding with the recent launch of European Community Organizing Network’s new report on ‘The Power of Organizing’ this article discusses a form of Transformative Organizing that enables the needed transformation of both the individual and society necessary for large scale systemic change.

A Future for All of Us; Butterfly Lab for Immigrant Narrative Strategy, Race Forward

“Whether you are an advocate or artist or thinking about how to apply narrative or cultural strategy for the first time, this new report on Immigrant Narrative Strategies is designed to help you think and act at multiple levels —locally, regionally, and nationally.”

Releasing New Data on Civic Language Perceptions, Kristen Cambell, Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement (PACE)

PACE partnered with Citizen Data to conduct a survey of 5,000 registered voters to understand people’s perceptions of the language associated with “civic engagement and democracy work.” They recently released their data on 21 commonly used terms, and are offering mini grants to support others to dig into the data to surface new findings, and create “bite-sized” content.

A Call to Connection, The Einhorn Collaborative, The Sacred Design Lab, and The Greater Good Science Center

The Einhorn Collaborative commissioned A Call to Connection to help leaders in multiple sectors better understand how vital human connection is to effectively address the challenges of our time. “Weaving together extensive scientific findings, insights from ancient wisdom traditions, beautiful stories, and concrete practices, this primer captures why and how human connection is a necessary and often missing ingredient in many of our efforts to ignite positive social change.”

The Pause, Newsletter of Pádraig Ó Tuama with On Being

Great newsletter to check out! This edition focuses on how even in times of conflict and upheaval, we can train our energy and attention on wonder not wounding; on awe, not war. Links to the recent re-airing of an interview with the esteemed astrophysicist Mario Livio, who spent 24 years working at the Space Telescope Science Institute of the Hubble Telescope. Shares his views of how the languages of art, science, and wonder can open up the human condition to the magnitude of the fact that we are here at all.

WATCHING

The Neuroscience of Trauma and Chronic Stress, Beyond Conflict

As a part of the March Brain Awareness Week of the Dana Foundation, you can re-watch this great panel discussion on how trauma and chronic stress impact the brain, including Vivian Khedari DePierro, Mike Niconchuk and moderated by Sloka Iyengar.

Shifting Mindsets to Shift Development Systems, Laurel Patterson, Head SDG Integration, UNDP

The UNDP describes a new approach to systems change with a focus on inner transformation, highlighting the fact that the ways social divisions, short-termism and siloed ways of responding to interconnected issues are no longer working. They are partnering with the Presencing Institute to help open new spaces to connect and make sense of what we’re all seeing and experiencing. Embedded in the article is a link to a series of videos on “awareness-based collective action”

Reframing History: A Conversation at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History

You can re-watch the launch of the report on Reframing History, including a panel of historians and museum curators, including Clint Smith author of How the Word is Passed and the head of the Hard Histories program at Johns Hopkins who shared the inspiring tagline: “History tells us how we got here. Hard Histories show us a way forward.”

LISTENING

How to Change the World, Podcast: Hidden Brain

Great interview highlighting the research of Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan on why nonviolent civil resistance works. “Pop culture and conventional history often teach us that violence is the most effective way to produce change. But is that common assumption actually true?”

Probing the Past: How Companies can Address Historical Transgressions, Podcast: The Crux

In this episode Dr. Sarah Federman discusses why she feels every Fortune 500 company should hire a historian an how understanding the past contributes to today’s DEI efforts and the need to accept responsibility, understand the past and respond meaningfully.

Cynefin, Sense Making & Complexity, Podcast: The Deep Dive

Conversation with Dave Snowden, creator of the Cynefin Framework about a range of social change issues, ways of solving complex problems and sensemaking.

INTERESTING TWEETS

The recent Arnold Schwarzenegger video appealing to Russians was given a lot of attention on social media. This is an overview of a social science study on the real persuasive impact of his messages given our polarized context.

Overview of new academic paper on how that parties to a conflict systematically mis-predict our counterparts emotions, specifically feelings of self-threat.

Reflections on Pastor Andy Stanley’s recent remarks to the Georgia House of Representatives. “Do you love the state of Georgia more than you love your party? If not, maybe you should do something else. Disagreement is always going to be there. Disunity is a choice.”

Great narrative advice on why it’s important to NOT amplify the messages you want people to forget.

Western States Center breaks down the recently released Southern Poverty Law Center’s Annual Year in Hate and Extremism Report.

THE VISTA: January 2022

WHAT WE’RE READING, WATCHING & LISTENING TO AT HORIZONS

There are so many wonderful insights and ideas that inspire us at The Horizons Project, helping to make sense of what’s happening, what’s needed, what’s possible and ways of working within a complex system. Once a month we share just a sampling of the breadth of resources, tools, reflections, and diverse perspectives that we hope will offer you some food for thought as well.

READING

Coordinates of Speculative Solidarity

By: Barbara Adams as part of UNHCR’s Project Unsung

“Solidarity has a speculative character and is fundamentally a horizontal activity with its focus on liberation, justice, and the creative processes of world- and future-building—projects that are never complete. The horizon is always present in the landscape, reminding us that there are things beyond what is visible from a particular location. As a coordinate central to perspective and orientation, the horizon is vital to successful navigation. As we move toward the horizon it remains “over there,” showing us that there are limits to what we can know in advance. However, rather than frustrating our efforts, horizons represent possibilities.”

The Relational Work of Systems Change

By: Katherine Milligan, Juanity Zerda and John Kania at the Collective Change Lab

“People who work with collective impact efforts are all actors in the systems they are trying to change, and that change must begin from within. The process starts with examining biases, assumptions, and blind spots; reckoning with privilege and our role in perpetuating inequities; and creating the inner capacity to let go of being in control. But inner change is also a relational and iterative process: The individual shifts the collective, the collective shifts the individual, and on and on it goes. That interplay is what allows us to generate insight, create opportunities, and see the potential for transformation.”

6 Key Practices for Sensemaking

By: David McLean on LinkedIn

This post highlights the work of Harold Jarche and is chock full of tips on how to deal with volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity.

By: Nat Kendall-Taylor at Frameworks Institute

“Being smart and right is getting in the way of moving hearts and minds towards positive social change…Speaking to what people are worried about resonates, while rhetorical quips and barbs make it seem like communicators don’t get the point, or worse, that they don’t care. Instead of defending the definition of Critical Race Theory, communicators could have pivoted to discussions about the importance of having an education system that prepares children for the world they will inherit, or of the role of having children realize their potential for the future prosperity of our country.”

After the Tide: Critical Race Theory in 2021

By: Baratunde Thurston on Puck

“So, I want us to stop talking about ‘critical race theory’ and start talking about what it means to love this country. I want us to stop burying our heads when someone shares an unflattering truth and instead embrace the discomfort and recognize it as a sign of growth. I want us to stop talking about ‘freedom’ as if it means denying the truth and instead remember that living a lie is what holds us captive, and the truth is what sets us free. I’m ready to get to the part of the American story where we have processed our pain and used it to forge a stronger nation, where we can heal from our historic traumas and focus our energies on building that ever-elusive multi-racial democracy where everyone feels like they belong. But we cannot heal from injuries we do not acknowledge. We cannot grow from pain we refuse to feel. Let’s know America. Let’s love America. Let’s grow America.”

To Tackle Racial Justice, Organizing Must Change

By: Daniel Martinez HoSang, LeeAnne Hall and Libero Della Piana in The Forge

This provocative read names how internal conflicts can show up within racial justice movements and offers concrete advice on creating an “organizational culture with more calling-in than calling-out.”

Just Look Up: 10 Strategies to Defeat Authoritarianism

By: Deepak Bhargava and Harry Hanbury

“The gravity of the threat demands a reorientation of energy from organizations and individuals to prioritize the fight to preserve democracy. Unless it is addressed, there is little prospect of progress on other issues in the years to come. The fate of each progressive issue and constituency is now bound together. We might even imagine a practice of “tithing for democracy” — finding a way for all of us, whatever our role and work, to devote a significant portion of our time to address the democracy crisis, which has become the paramount issue of our time. We may each make different kinds of contributions, but there’s no way to honorably keep on with business as usual in the face of the current crisis. We’ll explore a wide variety of possible approaches with the understanding that there’s no silver bullet or quick fix for such a deep-rooted problem.”

Strengthening Local Government Against Bigoted and Anti-Democracy Movements

The Western States Center released a new resource for Local Governments on how to counter groups working to undermine democracy and counter bigoted political violence. “Local leaders have the power to confront hate and bigotry. Many have shown bravery and commitment in working to counter these dangerous forces in their communities….we hope these recommendations provide one more tool to support these critical efforts.”

The 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer

The 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer was recently released with the study results of levels of trust in business, governments, NGOs and media. Across every issue, and by huge margins, people indicated they want more business engagement and accountability in responding to societal problems, especially climate change and rising inequality.

LISTENING

Podcast Undistracted: “This Big Old Lie”

The author of The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together, Heather McGhee sits down with host Brittany Packnett Cunningham to explain her research, the “hypnotic racial story” fueling American injustice, and how we can do better.

Podcast Scholars Strategy Network: Reflecting on Two Years of Trauma

Dr. Maurice Stevens, from Ohio State University, reflects on how Americans react and respond to traumatic events both as individuals as groups, and on how we can better connect amidst the current chaos.

Fear and Scapegoating in the Time of Pandemics

A podcast interview with Yale Professor Nicholas Christakis, director of the Human Nature Lab, on the connection between pandemics and our need to assign blame.

Podcast StoryCorps: One Small Step

In this episode, StoryCorps shares examples of people sitting down and talking about what shapes their beliefs and what shapes us as humans. StoryCorps founder Dave Isay describes what he envisions for this new initiative, One Small Step.

If you like poetry, you’ll enjoy this reading by Krista Tippet of Jane Hirshfield’s poem “Let Them Not Say” which is so powerful and relevant even though she wrote it a couple years ago.

Let them not say: we did not see it.

We saw.

Let them not say: we did not hear it.

We heard.

Let them not say: they did not taste it.

We ate, we trembled.

Let them not say: it was not spoken, not written.

We spoke,

we witnessed with voices and hands.

Let them not say: they did nothing.

We did not-enough.

Let them say, as they must say something:

A kerosene beauty.

It burned.

Let them say we warmed ourselves by it,

read by its light, praised,

and it burned.

WATCHING

Unraveling Biases in the Brain

By: Dr. Emily Falk and Dr. Emile Bruneau at TEDxPenn

“How can we unravel the conflicting biases in our brain to work towards a more just and peaceful world? In this talk, Dr. Emily Falk honors Dr. Emile Bruneau’s work at Penn’s Neuroscience & Conflict lab, describing the opportunity to look closer into our unconscious biases, question them, and face discomfort to make a change in our communities and beyond.”

This documentary by Ideas Institute that brings together twelve Americans from across the ideological spectrum to participate in a dialogue experiment on political polarization. It’s an hour long and “tracks each participant as they voice their political opinions, come face to face with those holding different views, and, perhaps, forge a path to mutual understanding.” You can watch the trailer here, and watch the movie from their website.

Hope-Based Communications for Human Rights Activists

By: Thomas Coombes at TEDxMagdeburg

Coombes reflects on how “social change activists are very good at talking about what they are against, but less good at selling the change they want to see to the wider public.”

INTERESTING TWEETS

Kicking Off the Horizons Project

We are thrilled to announce that in January 2022, The Horizons Project has launched under the auspices of our fiscal sponsor, the New Venture Fund. We are very grateful for the support of Humanity United and the Packard Foundation to begin this next phase of the Project’s journey.

As systems-level organizers, we are committed to proactively sharing our insights and reflections as they emerge about how peacebuilders, social justice movement leaders and democracy advocates operate and can potentially collaborate more effectively. Over the course of many insightful conversations and deep reflections with colleagues and network leaders in 2021, we have compiled some of the key tension points within that ecosystem. We hope that this evolving list may help to illuminate how we can deepen our understanding of each other’s perspectives and continue to find common cause in the future.

- Calls for understanding, “healing divisions” and unity are often criticized as not addressing the root causes of the problems we are facing as a nation (e.g., inequality, racism, rising authoritarianism, etc.), or as being disconnected from those efforts. Meanwhile, more confrontational forms of direct action (protests, boycotts, strikes, etc.) can be misunderstood or seen as overly divisive and unhelpful. It can be hard to see how these approaches can be complementary.

- Peacebuilders and bridge-builders who feel the need to maintain “neutrality” can be seen as propping up the status quo and not in solidarity with movements calling for equal rights and justice. Meanwhile, activists’ “polarize to organize” approaches can be seen as creating overly simplistic binaries and vilifying the “other.”

- Certain approaches to “calling out” those who are causing harm, or are perceived to be causing harm, can erect walls between people and create simplistic categories of “good” and “bad”. Calling in, or “calling out done with love,” can be a way to address harm in a way that centers relationships over shame while offering people onramps to changing their behaviors.

- Tactics of engaging the “exhausted middle” (where complexity of thought may still be flourishing) are criticized as a waste of time because the mythical moderate/independent voter is seen as “wishy washy.” Instead, activating the base is prioritized, with less attention paid to how to reach people beyond the base.

- Toxic polarization may be recognized as a problem across the board, but there is blame, defensiveness and othering (based on a lot of trauma on all sides) that drives us back to our ingroups and prevents intra-group self-reflection and dialogue around dehumanizing behavior and tactics. Emphasizing how polarized we are can also be a self-fulling prophesy.

- Bridgebuilding efforts to address toxic polarization can lead to greater hostility and inequality if done without paying proper attention to power relationships and wider societal factors (e.g., active disinformation efforts, historical traumas and injustices). Meanwhile, focusing on reaching out across divisions can downplay the importance of intra-group work to shift norms and behaviors.

- Many want to “focus on the future” as a way of finding common ground and coming together around shared values. This can be deeply troubling and hurtful for those who feel that we need to first recognize past injustices and harms and finally confront the painful history of white supremacy that continues to bleed into our present. Yet, the future-oriented framing can also be off-putting to those who don’t want change (or fear change) – so any call to “build back better” or for “democratic renewal” are met with resistance because of nostalgia for the way things were in a romanticized past.

- We struggle with lack of shared definitions of terms, and we don’t acknowledge that humans make sense of the world in different ways based on the multiple narrative streams flowing within the ecosystem. What does peace and peacebuilding mean? Is it finding calm and togetherness? What about “justice?” There are many negative connotations (or simple lack of understanding) of peace, peacebuilding, democracy and social justice across different groups that impede our ability to find common purpose.

- What does “democracy” mean and is it a shared goal for the US anymore? For some, the focus is on pushing for renewed civic culture and to embed the values of respectful dialogue, tolerance and empathy within society. Many hear these calls for “civility” with cynicism. They are more concerned about power imbalances around race and class and building power to participate equally in society and to push back against undemocratic forces. Others understand calls for “inclusive” democracy as only for liberals that seek to exclude more conservative perspectives.

- There is existential dread that is flowing within our country, and we see how a different sense of urgency plays out in many of these debates. While many movements are working for those who feel a daily fear for their physical safety, this is juxtaposed with those who are also expressing fear of losing their way of life and/or feeling left behind in a changing society. Some don’t feel the same sense of urgency regarding the pace of change, the threats to our democracy, and/or have the luxury of not being as directly affected on a daily basis. This leads not only to a difference in tactics, but it can also cause resentment, distrust, and the inability to hear each other’s experience or find common cause.

There is truth and need in all these various approaches and perspectives. Yet, until we name and wrestle with these tensions within the ecosystem, we won’t be able to deal effectively with our trauma, better hold space within ingroups, and lessen the criticism and resentment towards outgroups who may nevertheless be potential allies. New tools and conversations are necessary to rediscover our shared, higher-level goals of upholding democracy and to prevent the very real threat of increasing levels of violent conflict. The Horizons team looks forward to working with our partners to continue to explore and expand on the current research and tools available to hold these tensions in such a way that we can better connect with each other, encourage innovation and avoid toxicity in our relationships.

Get a quick glimpse of The Horizons Projects’ areas of work in this graphic illustration from artist Adriana Fainstein! You can find more of Adriana’s work here.

Combatting Authoritarianism: The Skills and Infrastructure Needed to Organize Across Difference

*This article was written by co-Leads Julia Roig and Maria J. Stephan and was first published on Just Security.

As the United States celebrated Martin Luther King Day this January, Americans also confronted the reality of the recently failed attempt to pass voting rights legislation and the ongoing dysfunction of the national-level political system. With this defeat, many political analysts, academics, and organizers feel a growing sense of existential dread that the country is at a tipping point of democratic decline, including an alarming pushback against the struggle for racial justice. International IDEA’s recent report on the Global State of Democracy classified the United States as a backsliding democracy for the first time in its history. Yet, many other Americans feel the threat to democracy is being overblown, taking comfort that “our institutions will protect us,” as they did when President Joe Biden was sworn in a year ago despite a violent uprising to prevent the certification of the election results.

Institutions are made up of people, however, who are influenced and held accountable by citizens and peers. In fact, there was significant organizing and coordination between different groups during the presidency of Donald Trump and around the 2020 election, when it had become clear that he posed a clear and present danger to U.S. democracy and was actively seeking to stay in power by whatever means necessary. That mobilization generated the largest voter turnout in U.S. history and an organized, cross-partisan campaign to ensure that all votes were counted, that voters decided the outcome, and that there was a democratic transition.

Today, a similar organizing effort is needed to confront a threat that has mutated and is in many ways more challenging than what Americans faced in 2020.

Yet even with the many painful commemorations of January 6th, polls show that democracy is not top of mind for most Americans. When asked to rank their five biggest priorities for national leaders, only 6 percent of those polled mentioned democracy – instead voicing concerns for their health, finances, and overall sense of security. Those who are inspired to organize to protect democracy, have radically different views of the problem, with a large swath of the country still believing “the big lie” that the 2020 election was stolen. The country has become dangerously numb to all types of violence, but especially political violence, as many Americans report that violence would be justified to protect against the “evils” of their political adversaries.

Time to Face the Authoritarian Threat, and Organize Accordingly

With all these competing priorities and different perspectives of the seriousness of the threat, what is most needed in this moment are the skills and infrastructure capable of organizing across these many schisms to find common cause. This is in a sense, a peacebuilding approach to combatting authoritarianism: deploying savvy facilitation to convene groups and sectors to identify and act on shared goals; and, using a systems lens to determine the most strategic interventions to break down the burgeoning authoritarian ecosystem and build up the democratic bulwark in response. What would this look like in practice?

First, leaders of the many networks, coalitions, and communities that are already organizing around various social and political issues across the ideological spectrum should be brought together in cross-partisan settings with democracy experts to reflect on the true nature of the threat.

While Trump gets most of the attention because of his continual drumbeat about the “stolen election,” the slide towards authoritarianism does not unfold because of just one individual. Authoritarianism is a system comprised of different pillars of support, including governmental institutions (legislatures, courts), media outlets, religious organizations, businesses, security and paramilitary groups, financial backers, and cultural associations, etc. that provide authoritarians (and other powerholders) with the social, political, economic, coercive, and other means to stay in power.

A key feature of post-Cold War authoritarianism, as described by Ziblatt and Levitsky in “How Democracies Die,” is that democratic erosion happens subtly, gradually, and often “legally,” as democratically elected officials use legal and institutional means to subvert the very processes and institutions that brought them to power. This is happening at the state level, where GOP-controlled states have become laboratories of democratic backsliding. In Georgia, for example, the Republican-controlled legislature has given itself more control over the State Election Board and the ability to suspend county election officials.

But the larger and more diverse the movement is that comes together to counteract these forces, the more likely it is to succeed. In fact, research shows that the most successful democracy movements that have been able to stem the tide of authoritarianism in their countries have always included a coalition of Left and Center Right actors and networks.

The cross-partisan nature of mobilizing against authoritarianism, therefore, is crucial and yet particularly fraught given the levels of chronic, toxic polarization the country faces. There is an urgent need to support movement-building techniques that bring together unlikely bedfellows and allow for a diversity of different approaches to achieve a shared goal of upholding democracy.

Breaking Down Siloes and Embracing Tensions

Authoritarianism, like any oppressive system, thrives on divisions and disorientation. It is fueled by a rhetoric of us versus them and fortified by the creation of walls between people who might otherwise align and organize. One response to this phenomena in the United States has been the explosion of depolarization initiatives, operating under a theory of change that citizens need to listen to each other more, communicate across difference, and “bring down the temperature” so people can have civil debate and come together “across the aisle.” These are important efforts; and yet are often in direct tension with social and racial justice groups that are focused on addressing past and present harms targeting minority and other vulnerable groups and shifting power dynamics. Still other coalitions have formed as bipartisan platforms for strengthening democratic institutions, tackling election reform, gerrymandering, and advocating for needed legislation. These many efforts in the United States are unfolding in their siloes, and are approaching polarization, justice, and democracy from their different vantage points.

Polarization, in fact, may be a good thing. Sociologist George Lakey likens polarization to a blacksmith’s forge that heats up society, making it malleable to change. In some highly polarized contexts, like Germany and Italy during the 1930s, extreme polarization led to Nazism and fascism, and allowed for violent dehumanization and toxic othering. There were pockets of resistance in both places, but no broad-based coalitions materialized that could have provided a bulwark to extremism. A contrast is the United States in the highly polarized contexts of the 1930s and the 1960s, when polarization paved the way to the New Deal and a massive expansion of civil rights. Of course, polarization also paved the way to the Civil War in the 1860s, but that only illustrates that polarization is neutral – what matters to the outcome is how people organize, and the strategies and tactics they use to wield power together to channel the forces driving change.

Likewise, the existence of tensions within and between groups is not necessarily a bad thing – healthy tensions can lead to innovation and expanded opportunities. They can help balance the need to project urgency with the imperative of building relationships. Bill Moyer and George Lakey describe four main types of movement actors – radicals, reformers, organizers, and service providers. It is common for there to be tensions between radicals and reformers, between those working on the inside and those on the outside, and between those who focus more on dialogue and more on direct action. The challenge is how to navigate these tensions.

Part of the answer is to identify and support systems-level organizers who have access to and credibility with both radicals and reformers, and who can help establish lines of communication, build relationships, and identify common cause. Building broad-based movements takes organizers and facilitators capable of convening network leaders, helping groups understand the complementarity of approaches, and supporting learning across spaces. Breaking down these siloes and building connective tissue is what it will take to puncture the “divide and conquer” strategy of the authoritarian playbook.

Sustained Cross-Cause, Multi-Sectoral Movement Building as Antidote

There was a recognized threat to democracy before, during, and after the 2020 election, and the recognition was shared by many diverse groups who came together to organize at that time. Now that the threat has morphed and dispersed, the ability to sustain a cross-cause, multi-sectoral movement is a little more difficult, but no less urgent. There are notably few spaces where conservatives are being brought into strategic conversation with progressive and left-leaning groups (and vice versa) about how to respond to current threats to democracy, and even fewer that bring grassroots and national groups into the same conversation. Key networks like the Partnership for American Democracy, the TRUST Network, and the Bridge Alliance could facilitate such strategic planning and coordination.

Convening leaders from conservative groups like Americans for Prosperity with more progressive social justice networks and democracy groups, like Indivisible, could yield unexpected results. Base organizers like the Industrial Areas Foundation, People’s Action, and Faith in Action have the infrastructure and relationships to be able to reach core constituencies on democracy issues, particularly locally. The Race-Class Narrative is an empirically-backed messaging and organizing framework for mobilizing the progressive base, persuading the conflicted, and challenging opponents’ worldview by fusing economic prosperity for all directly to racial justice.

Although building coalitions across groups is important, equally important is work within groups that can address toxic and anti-democratic behaviors, like acting on the belief that the 2020 election was stolen. After all, social psychology research highlights the fact that people are more likely to change their behaviors when they see other members of their in-groups change their behavior.

The private sector, religious communities and veterans’ organizations will all be key actors in this multi-sectoral democracy movement, requiring strategic outreach and relationship-building between actors who may not often collaborate on other issues. But reaching a shared understanding of the democratic threat as a higher-order shared goal will require concerted organizing. In the lead-up to the 2020 election, business coalitions such as the Civic Alliance came out strongly in support of voting rights and took actions to help their employees exercise the right to vote. Influential coalitions like the Business Roundtable, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and the National Association of Manufacturers issued statements acknowledging the election results and calling for a peaceful transition of power. These same groups could use various levers to hold candidates, officials, and themselves accountable to basic democratic norms in the current context: all eligible voters should be able to vote, election administration and certification should be nonpartisan, and the outcome of elections should be determined by voters.

Religious groups are another key group that could be activated in defense of democracy, such as the important role played by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference during the Civil Rights movement. Coordinated direct action between African American and white evangelicals would be a powerful driver of change in the future, and there is great potential in collaborations between groups like Faith for Black Lives, Interfaith Action, American Awakening, Matthew 5:9, Sojourners, and Catholic networks like the Ignatian Solidarity Network. Veterans groups are an especially important voice to speak out against the infiltration of extremists elements within the military and security sectors; several organizations such as the Black Veterans Project, the Black Veteran Empowerment Council, and the Veterans Organizing Institute provide needed vehicles for cross-ideological relationships and collaboration.

The key to successful movement building to protect American democracy in this moment will be to identify what leverage these different communities have to incentivize good behavior and disincentivize and (nonviolently) punish bad behavior. And success requires all these different groups – progressive and conservative alike – to be able to see themselves as a part of a larger ecosystem capable of collective action against authoritarianism. The power of civil resistance comes through organized non-cooperation – denying the authoritarian system the human and material resources it needs to wield power and undermine democracy. When a significant number of people within these key pillars coordinate and plan together to stop providing support – workers go on strike, consumers organize boycotts, students stage walkouts, businesses stop supporting political candidates and media outlets that spread dangerous conspiracies, bureaucrats ignore or disobey unconstitutional and unlawful orders, etc. – authoritarians lose their power.

Organized broad-based movements and non-cooperation were key to ending apartheid in South Africa, dismantling communist tyranny in Central and Eastern Europe, ending Pinochet dictatorship in Chile, and dismantling Jim Crow. Americans can find inspiration in those moments in history and from other country contexts to remember that it is possible for citizens to organize for freedom, justice, equality, and democratic values – and to succeed.

There are challenges to achieving this kind of broad democracy movement in a country as large and diverse as the United States. The country is deeply divided. It has not adequately confronted the historical legacy of slavery and racial hierarchy. What is unhelpful is succumbing to a sense of fatalism, to believing that civil war or falling into the authoritarian abyss is inevitable — “the other big lie.” The most important peacebuilding approach and mindset required of all Americans right now is one of conviction, hope, and mutual respect, to know that change is possible when people find common purpose and take action together.

Seven Foreign Policy Issues to Watch In 2022

*This article contains contributions from Director of Partnerships and Outreach Tabatha Pilgrim-Thompson and was first published on InkStick.

“We Didn’t Start the Fire” is a column in collaboration with Foreign Policy for America’s NextGen network, a premier group of next generation foreign policy leaders committed to principled American engagement in the world. This column elevates the voices of diverse young leaders as they establish themselves as authorities in their areas of expertise and expose readers to new ideas and priorities. Here you can read about emergent perspectives, policies, risks, and opportunities that will shape the future of US foreign policy.

As the Biden-Harris administration enters its second year in office, it will grapple with formidable foreign policy challenges that affect the wellbeing of Americans and global citizens alike. Seven members of Foreign Policy for America’s NextGen Initiative highlight seven of these challenges, ranging from ending the COVID-19 pandemic to reducing dependence on fossil fuels to identifying Unidentified (and perhaps unidentifiable) Aerial Phenomena — not to mention getting national security officials past the Senate and into leadership roles in order to tackle all of these challenges.

1. ENDING THIS PANDEMIC AND PREPARING FOR THE NEXT ONE

As the world heads into the third year of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the Biden administration will be looking to end the current pandemic and invest in programs to prevent and respond to future pandemics. With vaccination rates plateauing and high-income countries consider authorizing fourth doses, the need to vaccinate low- and middle-income nations will become that much more critical, as will increased access to diagnostics, therapeutics, and PPE tools.

As we have seen time and again, inequitable access to vaccines led to the development of more lethal, more contagious, and more severe forms of the disease. Rapid and accurate tests will need to be brought to scale as the world becomes more dependent on negative test results to attend school, travel, and access essential health services. Shortages of tests seen in the United States are far more severe in less wealthy countries and will not improve without significant donor intervention. It will be especially exciting to track new therapeutics, like those that significantly lower the risk of severe disease in immune-compromised patients. Careful attention should be paid to existing therapies, like medical oxygen and steroids, to avoid supply chain stock outs.

RAPID AND ACCURATE TESTS WILL NEED TO BE BROUGHT TO SCALE AS THE WORLD BECOMES MORE DEPENDENT ON NEGATIVE TEST RESULTS TO ATTEND SCHOOL, TRAVEL, AND ACCESS ESSENTIAL HEALTH SERVICES.

This year will also see US bilateral and multilateral global health programs pivot from the immediate response to the current crisis to planning on how best to prevent, prepare, and respond to future pandemics. To be determined are how the US government will structure and resource pandemic preparedness programs at State and USAID, and the role of US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) headed by the former Africa CDC Chief, Dr. John Nkengasong, who has not yet been confirmed by the Senate. In the fall of 2022, the United States will host the Seventh Replenishment Conference of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the largest global health funder. The upcoming Replenishment Conference will bring together donor and implementing governments, private sector, civil society, and affected populations to rally resources to end the deadliest infectious diseases and invest in efforts to prevent the spread of future epidemics. The Global Fund’s ability to draw on its strengths of achieving results against HIV, TB and malaria, civil society inclusion, and strengthening health systems will lay the groundwork for future pandemic preparedness and response. This will be a significant opportunity for the Biden administration to diplomatically engage other donors to increase contributions in global health, an area where many other high-income donors have fallen short. Without leadership — diplomatic, political, and monetary — there will be no end to this, or future, pandemics.

Shannon Kellman is the Policy Director for Friends of the Global Fight Against AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

2. A CITIZEN-LED APPROACH TO REVITALIZING DEMOCRACY

The deterioration of freedoms under the guise of pandemic response, successful coups in places like Myanmar and Sudan, and a violent insurrection in one of the most well-established democracies signal that democratic decline is unlikely to abate in 2022 without significant course correction. With general elections in declining democracies like India, Brazil, and Hungary, deepening toxic polarization heading into the US midterms, and a never-ending global pandemic, it is evident that we are at a turning point. Democracy advocates around the world will have to organize in ways that they never have before.

Commentary surrounding the Summit for Democracy and the one-year anniversary of the January 6 insurrection provide exhaustive diagnoses of the problems facing the US and its democratic allies. Some proposed concrete solutions, including crafting country-specific agendas, pursuing electoral reform and establishing a formal global democracy alliance. Yet, many recommendations targeted governments and political party infrastructure and offered less detail for how civil society can organize for democracy globally and here at home in the United States. With so much at stake, we need an all-hands-on-deck approach.

A sustainable movement for democracy needs a global coalition of activists, peacebuilders, organizers, academics, and community leaders to create pressure for local, national, and global reforms that translate into meaningful action at the community level. It requires organizing within and outside of elections, cross-sector strategic and scenario planning and mobilizing people who represent diverse constituencies, ideologies, and geographies. This is a big ask, but we have seen this level of coordination (albeit imperfect) before for issues like racial justice, climate change, and, on a smaller scale, to protect the 2020 US election results. With renewed attention internationally and new investments domestically, previously siloed democracy champions have a new opportunity to come together, learn, and share experiences, and plan this global movement.

Tabatha Pilgrim Thompson is the Director for Partnerships and Outreach at The Horizons Project, a new initiative focused on strengthening relationships among social justice activists, peacebuilders, and democracy advocates working to advance a just, pluralistic democracy in the United States.

3. OVERCOMING CONGRESSIONAL OBSTRUCTION TO NATIONAL SECURITY APPOINTMENTS

While not as headline-grabbing as other issues, one trend that will have major foreign policy implications in 2022 is the Congress’s refusal to confirm necessary staffing to national security positions. The Partnership for Public Service found that just over half of key Senate-confirmed positions, 97 out of 173, were filled as of Dec. 31, 2021. In part, this is the fault of Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) who single-handedly held up a number of positions due to disagreements over the Biden administration’s waiver of NordStream 2 sanctions. While Senator Cruz and Majority Leader Chuck Schumer were able to find an agreement to move forward with confirmations, it only takes one senator to keep these jobs vacant.

This slowdown in appointments creates a variety of problems that often lurk in the background of headlines. France recalled its ambassador to the US over the cancellation of a submarine contract related to AUKUS. How might have that situation been different if we had had an ambassador in Paris or an Assistant Secretary for European and Eurasian Affairs at the State Department? Potentially to avoid these issues, the president has grown the staff of the National Security Council (NSC) to approximately 350, but the impact of growing the NSC is unclear. America needs these key national security and foreign policy positions filled now.

Grant Haver is the host of the Next in Foreign Policy podcast, podcast producer and new content coordinator at TRG Media, and Senior Fellow for National Security at the Rainey Center.

4. MITIGATING THE IMPACT OF FOSSIL FUEL DEPENDENCE

The pain of global dependence on fossil fuels will increase, with many domestic fuel issues exacerbating social unrest and bubbling up to become international security issues and humanitarian crises. First, there is the post-COVID demand recovery outpacing supply, increasing fuel costs, and angering consumers. Second, there is the volatility of geopolitics mixed with fossil fuel dependence, resulting in some groups harnessing the demand for fuel to impose their will. Any combination of these two factors makes fuel shortages a potent weapon.

WHILE FUEL MAY NOT BE THE DIRECT CAUSE OF SOME OF THESE PROBLEMS, THE WORLD MAY REALLY START TO FEEL THE NEED FOR ENERGY DIVERSIFICATION THIS YEAR.

Kazakhstan is a good example of what may be in store for 2022. What started as a protest over increased fuel prices grew into a humanitarian crisis stemming from a violent crackdown and internet blackout. Russian military involvement, through the Collective Security Treaty Organization, unnerved the West as experts initially speculated whether Russia’s military would leave. There is also Yemen, where potential rebel control over the oil-rich city, Marib, could financially legitimate Houthi governance over the country. In Haiti, gangs cut off fuel supplies in October 2021 to provoke domestic chaos amidst the turmoil sparked by the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse. With the end of the assassinated president’s term nearing in February, some are concerned over the potential flash point this could create, forcing more refugees to the US border. If the gangs weaponized fuel once, they may do it again.

While fuel may not be the direct cause of some of these problems, the world may really start to feel the need for energy diversification this year.

April Arnold is a Senior Nonproliferation Adviser for Culmen International, where she advises the Department of Energy’s Office of Nuclear Smuggling Detection and Deterrence. She is currently pursuing her MA in Sustainable Energy at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.

5. REVIVING THE IRAN NUCLEAR DEAL

After a full year of stop-and-go diplomacy, 2022 could finally be the year that the United States and Iran return to full compliance with the Iran nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The JCPOA put into place the most stringent nonproliferation restrictions on a country in history until the Trump administration withdrew in 2018 and reopened the nuclear crisis with a failed “maximum pressure” policy. In response, Iran increased its nuclear leverage by reinstalling advanced centrifuges and stockpiling uranium up to 60% enriched. For a nuclear weapon, 90% enrichment is required, but under the deal, Iran can not surpass 3.67%.

In 2022, the reality that a diplomatic agreement is in the interest of the United States, Iran, and global security will not change. CIA Director Bill Burns has said there’s no evidence Iran intends to build a nuclear weapon while State Department spokesperson Ned Price has stated that Iran has made “modest progress” since the negotiations in late December 2021. We should, therefore, remain optimistic. Still, negotiators need to move faster as there are two looming hurdles ahead: Iran’s growing stockpile of highly enriched uranium and increasing technical knowledge, and the political chaos of midterm elections in the United States. Tehran is also demanding assurances that the US won’t withdraw, again, under a future president. Meanwhile, the Iranian people continue to suffer under corruption at home, economic sanctions from abroad, and an ongoing pandemic. A return to the JCPOA, or at least an interim deal to give diplomats breathing room, cannot come soon enough for all involved.

Shahed Ghoreishi is a Middle East Analyst and communications consultant.

6. REPEALING ANTIQUATED WAR AUTHORIZATIONS

In 2022, expect Congress to debate whether to reclaim its ever-eroding constitutional war powers and withdraw far-reaching authorizations for the use of military force. Soon after withdrawing US troops from Afghanistan, President Joe Biden said, “for the first time in 20 years the United States is not at war.” However, the open-ended laws that authorized the Global War on Terror (GWOT) and the Iraq war remain on the books. Congress will likely consider whether to repeal standing authorizations for the use of military force this year. Recent revelations of widespread civilian casualties from airstrikes conducted under GWOT and Iraq war authorizations make Congress’s efforts to rein in executive uses of military force all the more important.

Last summer, Biden announced his support for a repeal of the 2002 Iraq war authorization. The House of Representatives then passed Representative Barbara Lee’s bill to repeal the Iraq war authorization. Schumer soon after promised a 2021 Senate vote on a bipartisan proposal to repeal two laws authorizing the Gulf War and Iraq War. The vote, however, was delayed amid negotiations around the year’s largest defense policy bill. If the Senate finally votes on the repeal, it will likely pass, teeing up a debate over the 2001 war on terror authorization. Congress may also try to update the War Powers Resolution, a Vietnam War-era law that governs when the president may conduct military operations and what the president must report to Congress.

John Ramming Chappell is a J.D. and M.S. in Foreign Service candidate focusing on human rights and national security law at Georgetown University.

7. FINDING A NEW APPROACH TO UNIDENTIFIED AERIAL PHENOMENA

Perhaps the most fascinating trend in national security in the last year was increasing executive and congressional interest in the topic of Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (UAP). Following the bombshell 2017 revelations in the New York Times that the Pentagon had concealed an ongoing UAP monitoring effort, public interest has grown regarding repeated incursions into protected US airspace. A June 2021 unclassified report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) investigated 144 incident reports from 2004 through 2021, and 18 reports included what ODNI termed “unusual UAP movement patterns or flight characteristics” — including movement that defied physics and craft that operated without visible propulsion systems or emitted radio frequency energy. In addition, no evidence was found that any of the investigated cases could be attributed to a foreign adversary. As such, the report concluded that “UAP clearly pose a safety of flight issue and may pose a challenge to US national security.”

When asked about the report, Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines recently remarked that the obvious question remains, “…is there something else that we simply do not understand, that might come extraterrestrially?” Haines’ remarks seem to reflect a growing tone shift within the US government at both the executive and congressional levels. The Rubio-Gillibrand-Gallego UAP Amendment included in the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act authorized the first publicly acknowledged UAP office since the 1969 termination of the US Air Force’s controversial Project Blue Book.

While Air Force Regulation 200-2 prohibited the public release of UAP incident reports without a conventional explanation, the new UAP office will provide annual unclassified briefings and biannual classified briefings to Congress. Regardless of the explanation(s) behind these phenomena, the UAP issue represents an ongoing threat to US territorial sovereignty that must not be silenced due to the decades-old stigma attached to the topic.

Katie Howland, MPH, is an award-winning humanitarian with experience managing programs related to genocide response, literacy, and global health across the Middle East and Africa. She has been recognized as a 2021 National Security Out Leader, 2020 Aerie Changemaker, and a 2019 Nonprofit Visionary of the Year finalist by San Diego Magazine.

The Freedom Struggle in Florida

*This article by Chief Organizer Maria J. Stephan was first published May 14 on Salon.

The situation in Florida clearly represents a threat to American democracy.

Florida has become the epicenter of a struggle between authoritarianism and those committed to freedom and justice for all. Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis has cast doubt on the legitimacy of the 2020 election, actively campaigned for election deniers, embraced divide-and-rule politics, and enacted extreme policies that gut fundamental freedoms enshrined in Florida’s and the US Constitution. These policies, grounded in racial resentment, misogyny, homophobia, and the punishment of opponents using state power, come straight from the global authoritarian playbook and are already spreading from Florida to other state legislatures across the country. Attacks on fundamental rights and freedoms are only likely to accelerate should DeSantis’ clear 2024 presidential ambitions be realized.

But Floridians are not sitting idly by.

Daily walkouts, sit-ins, marches and teach-ins led by students, teachers, parents, and other civic groups are happening across the state. People are sounding the alarm about the existential threat to US democracy DeSantis represents, while mobilizing around an alternative vision of a Florida for all. Stopping DeSantis’ march to the White House will take a united democratic front of movements, labor organizers, business and faith leaders, veterans’ groups, and exile communities both inside Florida and across state borders. Beyond that, addressing the deeper roots of authoritarianism in America will require an even bigger and bolder movement that makes the triumph of a pluralistic, multi-racial democracy a generational achievement.

Part I: The Authoritarian Playbook

Twenty-first-century authoritarian leaders follow a similar playbook: build power by demonizing the “other,” then use that power to punish any opposition and cut off any ways of threatening their power, typically by undermining elections, capturing democratic institutions, and neutralizing dissent.

Demonizing and dehumanizing the other is the first step. Would-be autocrats tap into people’s fears related to safety, status, and well-being, and create scapegoats among marginalized communities. They establish these “others” as irredeemable enemies and argue that state power is necessary to suppress their threat. This strategy both mobilizes autocrats’ supporters and suppresses their potential opponents.

After attaining and consolidating power through this divide-and-rule strategy of “othering,” autocrats seek to then ensure that no challenge to them can stand by using state power to punish opponents, undermine civil and political rights, and hollow out accountability institutions like independent courts or free and fair elections. This is often done subtly and legally, using democratic means to gut the very essence of democracy.

Attacking fundamental civil and political rights, such as the freedoms of assembly and speech, is a key part of this strategy. Often justified on grounds of “protecting law and order” and “preserving the peace”, anti-protest laws have been expanding rapidly around the world. Nicaragua’s dictator Daniel Ortega has passed “anti-terrorism” laws to target those who protest his regime, while Cuba’s newest criminal code expands the criteria for prosecution and increases the penalties for violations. Other autocrats have attacked free speech in higher education, a historic bastion of dissent. In Hungary, Victor Orban pushed out Central European University based on anti-Semitic far-right tropes. Similar attacks are occurring in Mexico, Turkey, and Nicaragua.

Meanwhile, restricting women’s reproductive rights is commonplace among authoritarian governments. In recent years a number of democratic backsliding countries have reduced or limited access to abortion, including Poland, Hungary, and Brazil.

Often, autocratic leaders will embrace or turn a blind eye to political violence. They will refuse to denounce conspiracy theories (such as the “great replacement theory” that leftists and minorities are out to strip whites of power, that the LGBTQ+ community is responsible for “grooming” or harming children, or that free and fair elections have been rigged) until those theories become mainstream and pave the way to political violence

Ron DeSantis has embraced all these elements of the authoritarian playbook. The eerie similarity to global autocrats is no coincidence. Like authoritarians around the world, DeSantis and the GOP leadership have been directly inspired by global autocrats, and have developed a particularly special relationship with Hungary’s far-right leader, Viktor Orban.

The impact of this relationship is clear in DeSantis’ particular politics of divide and rule. Nine months after Hungary’s government passed a law cracking down on LGBTQ+ rights, DeSantis followed suit. Orban described his country’s anti-LGBTQ+ law as an effort to prevent gay people from preying on children. Similarly, DeSantis’ press secretary, Christina Pushaw described Florida’s Parental Rights in Education law (the “Don’t Say Gay” law), as an “anti-grooming bill,” referring to a common slur directed at LGBTQ+ people.