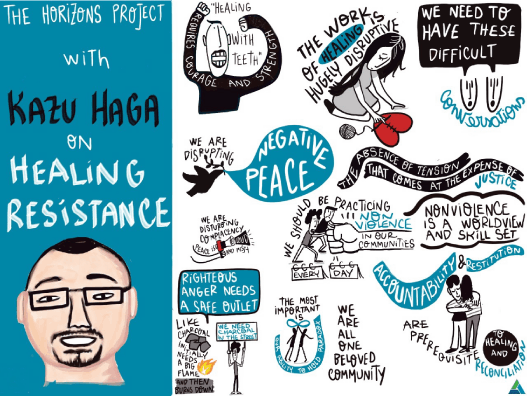

Nonviolence is a cornerstone of activism and radical change, but less attention has been given to the restorative power of nonviolent resistance. In this recent Horizons Project event, Senior Advisor Maria J. Stephan interviewed author and Kingian nonviolence practitioner Kazu Haga on his book, Healing Resistance: A Radically Different Response to Harm. The event publicly launched the Horizons Project.

Click here to watch the whole event.

Kazu Haga is the founder and coordinator of East Point Peace Academy in Oakland, California. He was introduced to social change and nonviolence in 1998 when he participated in a six-month interfaith walking pilgrimage from Massachusetts to New Orleans to retrace the Middle Passage and the slave trade in the United States. He began a lifelong path of social justice work. For over twenty years, he has practiced and taught Kingian Nonviolence – a philosophy of nonviolent conflict reconciliation based on the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, and the organizing strategy used during the Civil Rights Movement. This discussion explores Haga’s philosophy and experience with Kingian Nonviolence training, social justice work, and conflict reconciliation. It centers the question: how can nonviolent resistance challenge injustices while fostering societal healing?

This online event was co-hosted with Humanity United, East Point Peace Academy, On Earth Peace, and the Kingian Nonviolence Network. This interview was condensed and edited for clarity. A full transcript can be found here.

Why did you feel compelled to write this book? What do you mean by “healing with teeth” and how does it motivate healing resistance work?

In progressive circles, the concept of healing has almost become mainstream, and in a way, that’s good, right? We want nonviolence, healing justice, all these things, to become mainstream. And at the same time, whenever something becomes mainstream, there’s a danger to it because it loses some of the essence. Oftentimes, when people talk about healing modalities, those conversations are happening in the absence of an analysis around systemic harm and historical harm. We don’t realize that a lot of the harm that people are living with today that we have to heal through is the result of a system that has brought violence to certain communities and not to other communities for 500 years, and that those systems still exist, and that those systems are continuing to cause harm in this moment.

If we don’t have the fierceness and the power and the teeth to really challenge these systems that are causing so much harm today, then we can be healing people’s traumas all we want, but these systems are causing more trauma at a faster rate than we can ever heal them on a one-to-one personal basis.

What do you mean by disrupting negative peace? What are some of the challenges and misperceptions of disrupting peace in healing work?

The example that I always use when I talk about negative peace is the story of Autherine Lucy, who was the first Black student ever to go to the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. As you can imagine, the first day that a Black student showed up at the University of Alabama, which had always been a segregated school in the South in Alabama in Tuscaloosa, there was violence. A riot broke out, and the KKK showed up, and a mob surrounded the car she was traveling in and climbed up on top of it. And to respond to this violence, the University expelled Autherine Lucy, saying this was her fault and so they kicked her out. And the next day, because she was no longer on campus, the riots had stopped, and the local newspaper ran a headline that read “Things are Quiet in Tuscaloosa. Today, there is peace on the campus of the University of Alabama.” And in response to that incident, Doctor King gave one of my all-time favorite sermons. The sermon is called “When Peace Becomes Obnoxious,” and in that sermon, he said that what happened at the campus the next morning wasn’t a real peace. He called it a negative peace, which is a term that was coined by peace educator Johan Galtung.

Dr. King said, “Negative peace is the absence of tension that comes at the expense of justice.” If someone is screaming at my face, and I punch them and knock them out, they’re no longer screaming at me, so it’s quiet. Did I just create peace? As absurd as that thought is, because of our gross misunderstanding in our society of what peace is, we think as long as things are quiet, then things are peaceful. We justify these crazy ways of trying to achieve “peace,” so we go to war to try to create peace, we incarcerate people to try to create peace, we lock up all the protesters to try to create peace and that’s not a path to creating real peace. At best, what it creates is negative peace, it’s a very temporary surface-level thing by repressing the real issues that need to be brought to the surface.

One of the things that I always talk about is how Doctor King was arrested 29 times in his life, and a bunch of those times, he was charged with disturbing the peace, and it’s what nonviolent activists are oftentimes accused of. But we have to realize that in nonviolence when we use nonviolent tactics to bring issues to the surface, we’re not disturbing the peace, we’re disturbing complacency, and we’re disturbing the normalization of violence.

The path to real peace, which includes justice for all people, is going to be disruptive, it’s a messy process. Peace is a messy process, and I think that’s a lot of the misunderstandings that we need to kind of dispel around the idea of peace, and the idea of nonviolence, like, peace isn’t just about harmony. It’s about justice, and justice is loud, especially in a society that has normalized so much injustice.

How do you balance the need for accountability and the recognition of harm while at the same time creating a space and recognizing the humanity of the other? How do we create safe spaces for anger and rage?

Oftentimes, we wait until there’s a riot, or we wait until someone’s been killed, and then we ask, ‘well, what can nonviolence do about it?’ And there’s a lot that nonviolence needs to do in response to it, but that’s almost like asking someone to wait until you’re in a fight to start learning about martial arts and self-defense. It’s a little late in the game,” Haga said. “A lot of the work that we try to do is what we are doing in our communities every single day so that when these heightened moments happen, we’re already grounded.

When a community has faced nothing but violence from the state for 400 years, every bit of that rage gets poured out into the streets. Regardless of how it gets expressed, it is legitimate, and it is righteous. I think as community leaders, we need to create more safe containers for that rage to be seen and for that rage to be honored because if we don’t create safe containers for that to be released, it’s going to get released on a gas station, and there’s no point in talking about whether it’s right or wrong or effective or not because it’s inevitable.

I think what that means in movement contexts is before going into the demonstration, relying heavily on healers and faith leaders and people who have those skills to hold grief circles, to use art to express our rage, to create spaces where we’re sitting in a circle crying together, screaming together, grieving together in a container where that expression of rage isn’t going to be misinterpreted, and then we’re going to get tear-gassed as a result of it. Because that can be retraumatizing. It’s important for us to create these spaces where rage and grief can be expressed, but if we’re getting arrested while we’re doing that can be retraumatizing.

You emphasize the importance of training and preparation throughout your book. What are the collective muscles that we need built up individually and as a society? How do we think about training and practically flexing those muscles to be prepared for these moments?

We know that when our trauma is triggered, we see everything in black and white because that’s what survival is about. Survival is about black and white. It’s about you’re either a threat to my life or you’re not, and so it makes sense from a survival mechanism, but the reality is that our world is never black and white. Our ability to see nuance is so important in seeing the truth for what it is, and so anything we can do to see nuance, anything we can practice to help regulate our emotions – all of that I think has to be incorporated in this kind of new generation of nonviolent direct action trainings.

How do you explicitly integrate anti-racism with Kingian nonviolence?

I think part of why racial healing and racial reconciliation feels impossible at times is because in a lot of the places where that conversation is happening, we skip the step of accountability and restitution and reparations. But reparations are a prerequisite to healing and reconciliation. Accountability has to be part of the process if we’re really going to heal through harm, and so I think if we’re really serious about racial healing and racial reconciliation in this country, we have to tell the truth of what happened and do what we can to repair the harm in a real concrete way.

Are these ideals for healing resistance difficult for the mainstream? What strategies do you recommend to help people have these difficult conversations?

The path to liberation is to actually go against the flow of what feels natural and to lean into suffering to lean into what hurts so that we can really face it,” Haga said. “It doesn’t feel natural for me to try to cultivate compassion for the person that hurt me, but that it turns out is the path to liberation.

It definitely goes against mainstream values, and I think the best we can do to kind of cross that chasm is to tell stories. People don’t remember theory, they remember stories, like what are the stories from your life you remember what it felt like for you that you had so much hatred and resentment towards someone that you couldn’t do anything like to move forward in your life. I think the more we can start telling our own stories, the more we can cross that gap.